Creativity and Lateral Thinking

Endangered Species: Once upon a time there was a little library. It was full of books and people loved it. Children spent many a happy hour browsing for little gems among its shelves. Alas, as often happens in fairy tales, things changed and the local authority found itself in dire financial straits. If the library was to be saved, the people would have to agree to a 0.7%  rise in local taxes. August the 2nd was scheduled as the voting day. The fate of the little library hang in the balance…

rise in local taxes. August the 2nd was scheduled as the voting day. The fate of the little library hang in the balance…

An uphill struggle: Things looked bleak. As soon as the date was announced, the ‘Tea Party’ movement, a vociferous and well-funded group, started campaigning in favour of a ‘No’ vote to the proposed tax rise. These people were well organised and it was soon evident that the focus had shifted from whether the library should be saved to something very different – whether one was for or against taxes. The answer to this is of course a no-brainer…

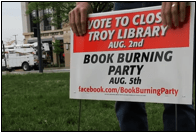

The campaign: Faced with imminent disaster, the supporters of the ‘Yes’ movement realised that a normal campaign would be doomed. It was time for something different. Something drastic. Something spectacular. Could lateral thinking be the answer? Then one of them had a brainwave: ‘Why not go to the opposite extreme? Never mind the library – let us burn those books!’ (I won’t spoil it for you – just click here to watch the clip.

The lessons: So what are the lessons to be gleaned from this amazing case? To me, there are at least 3 things worth  noting:

noting:

Framing: How an issue is framed can often determine what stand people take. It is all about playing to your strengths. Attention is a commodity in short supply and if your cause is right it is vital not to allow people to be distracted by irrelevant issues (e.g. Immigration scare-mongering as opposed to who is responsible for the plight of the economy).

Emotion: Arousing emotions is a great motivator. Anger is particularly potent (in Berger’s words ‘Make them mad – not sad!’). In this respect the ‘book burning’ idea was a stroke of genius as it clearly evokes images of Nazis burning books in Hitler’s evil regime. It was this visceral anger that motivated people to act – by posting comments, raising the issue in public forums etc.

Incongruity: To cut down on processing effort, our brain does not notice everything. It normally operates on autopilot, until something strikes it as strange, weird or out of place. Then it switches to high alert and things start to register properly. Notice how this was used twice; first with the ‘Book Burning Party’ and then once again when the whole story came out. Amazing! Moral: to attract attention, break a pattern!

The role of the media: Notice that a key component of the success of this (counter-) campaign was the media. The whole thing went viral and when the true identity of the ‘whackos’ was revealed, this led to a second wave of media coverage. Why was it so successful? The campaign ticks three items in Berger’s list of virality ingredients: ‘Public’ (it was very visible); ‘Triggers’ (whenever people saw books or a fireplace they were reminded of it) and ‘Emotion’. In Berger’s words – ‘When we care, we share’.

[jbox title=”References”]

Berger, J. (2013) Contagious. London: Simon & Schuster.

Ferrier, A. (2014) The Advertising Effect. South Melbourne, Oxford University Press.

Freedman, L. (2013) Strategy. New York, Oxford University Press.

Heath, C. & Heath, D. (2008) Made to Stick. London: Random House.

[/jbox]

2 Responses

eslwriter

Does this article connection with English language teaching?

27/10/2015

Nick Michelioudakis

Actually, I think it does - albeit indirectly. It has to do with Education in general. How you frame an issue (or indeed a task) may well determine how your students respond to it; using emotions may get your students more actively involved in a debate for instance; as for incongruity, I believe it's key in maintaining student motivation (e.g. by 'tweaking' an activity so that it feels strange / more creative). In my experience there is almost always a trade-off between the immediate usefulness of an idea (e.g. a specific activity which may only be applicable in a particular context) and how widely applicable it is (e.g. a classroom management tip which can be relevant to all levels / ages). This article contains ideas which fall into the latter category.

27/10/2015