By Michelle Shin

In 2010, Hawaii’s legislature and governor signed into law a bill that would extend the school day, first by an hour a day, later by another half hour addition. At the time, my sophomores groaned and protested since this would affect them while my seniors revelled in their “good luck.” It started a pretty big debate in my classroom—the pros and cons of a longer school day with many students bringing up valid and compelling concerns about this additional hour while a few, strong and confident, argued it was the right choice for education.

I watched them debate this in class, saw all the passion and noteworthy ideas flowing, and then the bell rang. In other words, plenty of grumbling, but then they leave the room and nothing changes. It was time to teach students that change has to start somewhere—even if it is small and one person’s opinion.

Thus began my “Letter to the Senator” assignment, which I titled because it rhymes and that makes it easier for students to remember, but they can write to any person who holds an elected office or who exert political power to induce change—their council member, mayor, local representative or senator, the governor, U.S. senator or representative—I’ve even had one student write to the Chief of Police.

At first, students think they have to tackle a “big” topic, something of recognized and weighty importance. But I tell them they should focus on something they feel passionate about and want to see action on whether that be renewable energy, immigration reform, or adding an extra stop sign on their street or synchronizing the traffic lights on a major avenue.

That first year, we all wrote to the local representative and senator for our school district on the topic of the extended school day since the students were so vested in that particular topic.

They could either support the bill and ask that their senator enact it or rebuke it and ask for a revision or a decision to revoke it. The next year, I opened the letter up to free choice in topic and who to write it to, and have since received letters that address diverse issues, like gay marriage (on both sides), the number and accessibility of DMV offices, funding for classrooms, a call for more investigation into how college tuition is spent by the universities, pleas to address the homeless situation in Waikiki, and two students (in separate classes) who were extremely passionate about how they should not have to pay extra car registration fees for owning modified cars.

These letters are not a long and arduous assignment, yet when I look at the students’ year-end writing portfolios, they are often the ones that best represent the voice of the student and which best speak to the heart of the reader. I feel this is because the assignment is very structured and not sprawling; students can intensely focus for one single-spaced page on a topic that they feel personally invested in and which they have persuasive ideas on.

The “Letter to the Senator” assignment asks for a persuasive, specific, well-written argument that appeals to logic and emotion and which is backed up with credible evidence and examples.

They must also include a feasible solution or suggestion at the end. We use this assignment to talk about ethos, pathos, and logos and how each appeal has its place in an effective argument, such as how they write and the words they choose to use reflect back on them and their credibility. If they are angry and outraged, I especially stress that being respectful and letting your argument win instead of your anger is part of the ethos that will compel a person to be on your side.

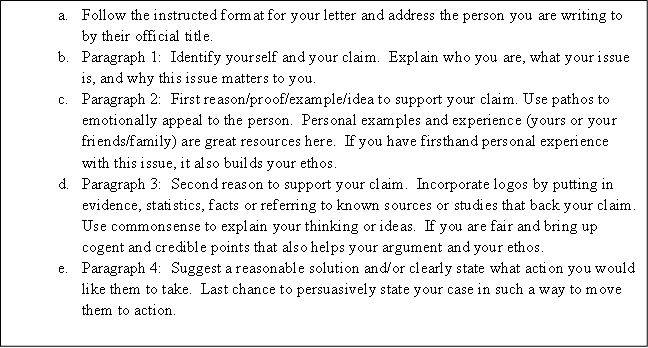

The general format breaks down like this:

With this assignment, instructors can easily add in a vocabulary component or change the format and have students create a short PSA or presentation based on their ideas and the materials gathered. This assignment has been very engaging and fun, a breath of fresh air between intense research papers or long literary analyses, and reminds the students that they have a voice and that elected officials are in office to listen to and serve them.

I emphasize to students that we can’t just be satisfied with the famous bumper sticker “No Vote, No Grumble”—we need to exercise all of our rights and that means speaking out as well.