Using Music to Break Down Barriers in the Classroom

“He who begins life with music will have this reflecting on his future like golden sunshine” (Z. Kodály).

What do you do when you have class of three year old mostly Spanish speaking children in a bilingual school and you are told you have to teach them music in English which you have never done before?

Well, first you panic, then you despair and then you get them to sing!

This is exactly what happened to me some years ago when, as a music teacher I was employed by a school in Montserrat School (FUHEM), Madrid.

It is said that music nourishes the soul. It can arouse emotions, it can motivate and it can pacify. As Shakespeare himself said in Twelfth Night, “If music be the food of love play on”.

There is an extensive body of neurological research which shows that our brain can function better when music is involved and it seems where our young children are concerned, the earlier children learn to understand and appreciate music and particularly rhythm and pitch, the easier it will be in later life to transfer this understanding to maths, literacy, language and social skills. Martina Huss and her research colleagues reinforces this: “The ability to perceive the alternation of strong and weak ‘beats’ (stressed and unstressed syllables) is critical for the efficient perception of phonology in language… as rhythm is more overt in music than in language, they suggest that early interventions based on musical games may offer previously unsuspected benefits for learning to read.” 1

Unfortunately, not everyone appreciates the value and power of music. We have all heard questions and statements such as, “Is it worth studying music? What for? Can anyone make a living through music? It’s very difficult to become a good performer” etc., implying that if music does not lead to some kind of vocation, then it is a waste of time and resources.

This is true in Spain, where it is not easy to be a music teacher. Music as a subject has disappeared in some schools, and where it remains, there is only one hour a week at best given over to it. As music teachers we need to be vocational and firmly believe in the importance of our work despite this situation; we mustn’t despair and lose our sense of purpose in this demanding job. In fact it is our love and devotion to music, which carries us through.

I feel very grateful that during my university days I was fortunate to lay my hands on the book “The Human Value of Musical Education,” (“El valor humano de la educación musical”) written by the great music educator Edgar Willems. This book not only created a great an impression on me but it has been a constant influence on my music teaching in music schools, kindergartens and primary schools. Since reading this book I now understand that the main objective of the subject of music at school is not to train musicians but to aid in the comprehensive development of the personality.

Many schools in our country are now trying to implement bilingual programmes at primary and secondary school levels and so many subjects are currently taught in English. This means that children who start kindergarten at the age of three arrive with little or no English and it is here where we have to start to lay the foundations of the language. When I started in my bilingual school, I quickly realised that my usual repertoire and especially the wonderful songs of M E Walsh were no longer suitable. I needed simple songs in English but as a Spaniard I knew very few. Thankfully the Internet became my assistant and before long, we were singing and dancing some nice songs.

I discovered that the children were able to pick up the tunes and the words quite quickly even though at first they did not know the meaning of the words. That didn’t matter as they were having fun and getting used to English pronunciation and the rhythm of the language. What did matter to me however, was that I had best quality music and appropriate songs for my repertoire.

One of the biggest aids which I found to help me in my music teaching was the musical programme initiated by Chris Jolly, the founder of Jolly learning Ltd and the promoter of the Jolly Phonics system for teaching children to read English. Chris Jolly was very aware of the importance of music when teaching children how to read and write (it is present in Jolly Phonics through the songs and movements), and so he decided to implement a music programme for British schools. He therefore commissioned Cirylla Rossell and David Vinden to design Jolly Music, a very well-planned and well-structured music programme of the English culture.

This programme is based on the methodology of Zoltán Kodály (1882 – 1967, pronounced kŏ-dī) who, according to the British Zoltán Kodály academy, was born in Hungary at a time when its language and culture was subservient to German and Austrian tradition. His passion for the rediscovery of the Hungarian spirit resulted in extensive folk-song research, which established a set of principles to follow in music education. He believed it was the birth right of every child to be able to express themselves through singing and through his method children are encouraging to sing traditional folk songs and nursery rhymes which are easy to sing and fit in with a child’s limited vocal range.

Given that in England the music teacher is the tutor and not a music specialist, they provide CDs, which include all of the recordings, so you do not need any musical background to use Jolly Music. It very useful for music teachers but also for English teachers who want to develop some musical skills and improve their teaching through music.

These popular songs, rhymes and games represent the musical and cultural heritage of the language and have endured for generations, therefore it is also important that they are passed on. The words in songs and rhymes tend to be slowed down as compared to everyday speech, and are structured and repetitive, making them easier for young children and non-English speakers to grasp.

Once I realised that music can cut through barriers and especially linguistic barriers I started to enjoy my job and to enjoy laying the foundation in English which would help my young students children to flourish later in their primary years.

Singing provides an active understanding of music (sense of pulse, pitch awareness, understanding of rhythm, etc.), as it is an internal skill. In addition, “Lullabies, song and rhymes of every culture carry the ‘signature’ melodies and inflections of a mother tongue, preparing a child’s ear, voice and brain for language.”2 This is why Kodály always focused on popular music of every culture.

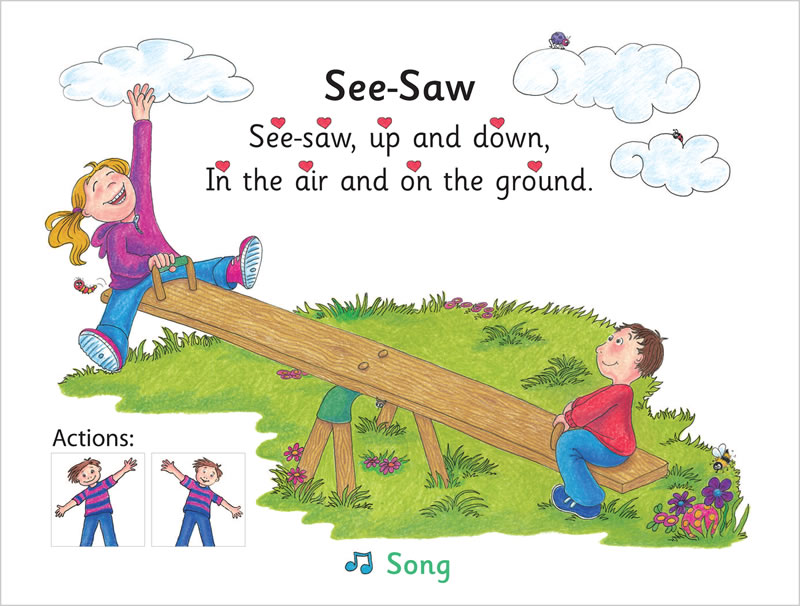

So now let’s have a look at the progression of a very simple song, “See-Saw.”

At first, we can sing this song with the movements stretching our arms. Even 3 year olds love it. There are only two pitches, sol and mi, with crotchets and quavers:

s m ss m / ss mm ss m //

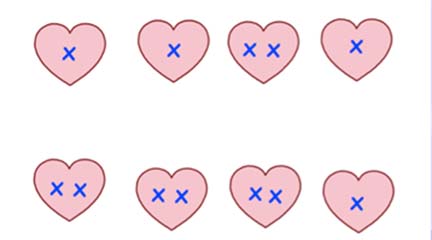

We will talk about the pulse afterwards, represented by the hearts, and we will write one or two crosses on each heart, depending on the rhythm given by the words.

Once we know the relation between pulse and rhythm, we can start talking about music theory, introducing crotchets and quavers related to the steady beat as follows:

We can finally introduce the stave at the end of the process once they learn that this song has only two pitches, sol and mi. Sol is on the second line of the stave (high) and mi on the first one (low).

In this song children become aware of the sense of pitch through movement, which provides a kinaesthetic link to the sound.

Hot: one crotchet clapping your hands (la – high pitch)

cross: one crotchet crossing your arms (sol – medium pitch)

buns: one crotchet tapping on your lap (fa – low pitch)

Crotchet rest.

Hot: one crotchet clapping your hands (la – high pitch)

cross: one crotchet crossing your arms (sol – medium pitch)

buns: one crotchet tapping on your lap (fa – low pitch)

Crotchet rest.

One a penny: 4 quavers tapping on your lap (fa – low pitch)

two a penny: 4 quavers tapping on your chest (sol – medium pitch)

Hot: one crotchet clapping your hands (la – high pitch)

cross: one crotchet crossing your arms (sol – medium pitch)

buns: one crotchet tapping on your lap (fa – low pitch)

Crotchet rest.

This is how we work unconsciously with pitch, rhythm and rests, the relation between beat and rhythm and the phonics (the sounds “H” and “U” don’t exist in Spanish), and later they will learn the musical elements connected with this experience, of which they were probably unaware.

I would like to finish this article with a quote by Kodály in order to encourage our musical work at school:

“Music is one of the most powerful forces for the uplifting of mankind, and he who renders it accessible to as many people as possible is a benefactor of humanity.” (Zoltan Kodály)

References

1Report on research into the dyslexic brain by Martina Huss, Usha Goswami, et al.. Martina Huss, John P. Verney, Tim Fosker, Natasha Mead, Usha Goswami, “Music, rhythm, rise time perceptions and developmental dyslexia: Perception of musical meter predicts reading and phonology,” Cortex (2011), 674-689.

2Sally Goddard Blythe, The Genius of Natural Childhood, (Hawthorn Press, 2011).