Teaching English in Russia: A Brief Guide

Why are you going there? It’s dangerous!” These were the words of my manager at the law firm in the UK where I had been working for the past three years. Moments earlier I had just handed in my resignation letter and announced that I was moving to Moscow where I had accepted a job as an English teacher. I had never visited Russia nor did I have any classroom teaching experience. Nevertheless, Russia was a country which I had longed to visit for many years and I was excited (albeit slightly daunted) to begin this new chapter in my life.

However, not everyone shared this excitement. In the weeks leading up to my departure I noticed three different types of reactions to my news. Upon hearing my news, one group of people would look at me with pity in their eyes as if I had told them that I had just been diagnosed with a terminal illness. The second group of people would usually stare at me with a look of genuine fear in their eyes like I had just told them that I was about to jump in front of a train. The third and final (and perhaps my favourite group) reacted with a bizarre sense of anger and confusion as though I had told them that I was a spy. For many, Russia remains a mystery. Indeed, in the words of Winston

Churchill:

“I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an

Winston S. Churchill

enigma.”

I looked forward to unwrapping the mystery that was Russia.

Unwrapping the Mystery of Russia

I have now lived and worked in Russia for over a year and, whilst there remains many layers of mystery to unwrap, I have been fortunate enough to peel back the first few layers and learn more about this remarkable country and its people. On this note, here are several humorous things I have observed during my time here:

- A Short Walk’: Russian people love walking. Far from the leisurely stroll to which I was accustomed in England, a Russian walk usually involves walking through a forest in sub-zero temperatures until you develop hypothermia.

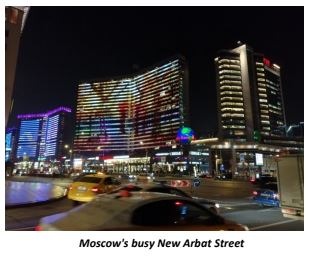

- “Passport please”: A second quirk to which I have had to grow accustomed in Russia is the enormity of bureaucracy necessary to contend with in order to complete the simplest of tasks. I once had to show my passport, wait for a handwritten ticket to be produced (I felt like Charlie from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory with my golden ticket), then climb up Moscow’s busy New Arbat Street four flights of stairs, just to collect a pair of headphones I had already ordered and paid for online.

- “Camouflage, camouflage and more camouflage”: Another thing which struck me upon arrival in Russia was the sheer number of security staff. Security is everywhere here: in supermarkets, shops, banks, museums and even parks. I should add that, compared to England, supermarket security staff are a force to be reckoned with. For example, one afternoon in a supermarket, the woman in front of me in the queue was dragged away by a camouflaged security guard to be questioned about the contents of a plastic bag she was holding which contained some meat. Her explanation that she had bought the meat elsewhere beforehand was apparently deemed insufficient!

The Life of an English Teacher in Russia

For the past year, I have been working in Russian schools as well as teaching adults in Moscow. It has been a thoroughly interesting experience.

The majority of my teaching experience to date has involved children. What I have found is that Russian children are no different from any other children around the world. Many are extremely smart and self-motivated, with a seemingly natural gift for languages. Others are perhaps less motivated and require more attention but are often no less intelligent than their peers. There is a huge demand for English here and Russian children (and their parents) are some of the most determined and ambitious I have come across.

However, as any school teacher will understand, it is not always plain sailing and controlling behavioural issues is an everyday reality. At one particular school (affectionately nicknamed ‘The Bearpit’), I had to break up a fight between a Russian and Georgian child (the two countries have not been on particularly friendly terms since the 2008 war), stop a child from suffocating himself with a plastic bag, and tell another child to stop pouring water onto a cold burger which he had placed in the centre of the classroom on the floor, as if it were a plant. This all happened within the space of a few months. The life of a English teacher in Russia is anything but boring.

Concluding Thoughts

Overall, I have had a remarkable year here teaching in one of the world’s most fascinating and misunderstood countries. Whilst there are of course things which I miss about my life in the UK, I have made Russia my new home and am enjoying every minute of it. For anyone who is debating whether or not to come and work here as an English teacher I would advise you to put aside your concerns and take the leap, you will not regret it.

Elliot Emery’s book “Why are you going there?” (Stories of an English teacher in Russia) is now available on Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com