Vocabulary Teaching Strategies for English Learners

It’s always the same, isn’t it? We do a lesson with all these fantastic words and phrases, which our students will need and find useful for years to come. They have actively been in involved in the lesson, asking the right questions and even starting to use the new vocabulary.

You walk away from the lesson with that rewarding feeling that we, as teachers, get from time to time – that feeling of achievement, progress, getting things done. Then comes the next lesson, and they’ve forgotten the lot.

What happened? If you’re a teacher with a reasonable amount of experience under your belt, you know not to panic. This is completely normal. It takes time to learn new vocabulary. It takes effort, repetition and sustained usage. However, there are ways of making things stick better.

The research on vocabulary learning

According to a lot of the research on vocabulary acquisition, using language in context is probably the best way to remember new words in a foreign language. Context, meaning and vocabulary all work together to solidify knowledge. Pouncing on the next opportunity to get our students to use vocabulary in context is something that I find myself doing regularly as a teacher.

Unfortunately, the classroom simply cannot always provide the natural context, where we can use each and every piece of vocabulary we deliver to our students. How can we orchestrate the lesson so that “unidentified item in the baggage area” comes up in context? What do you need to be talking about in order for your students to naturally produce the word “siphon”? It’s very clear that we need additional strategies to help them learn more efficiently. Fortunately, some work has been done on this.

Atkinson’s keyword method approach

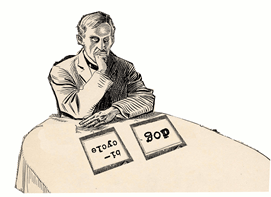

Back in the 70s, a lot of research was carried out in the psychological community on the power of memory. In one study, Gordon Bower1 asked his respondents to memorize sets of word pairs laid out in front of them (such as dog/bicycle).

They were given 20 of these word sets with just five seconds to look at each of them. Following that, they were given the first word as a cue and were asked to recall its pair.

At first they did poorly, remembering on average about 33% of the pairs. Then they were asked to create a strong image connecting the words (what Bower calls “image instruction”).

When the test was repeated after this “image instruction, there was a recall rate of 80% of the pairs; an increase from 33% to 80%. Impressive stuff – but what exactly was this “image instruction”? Well, it’s pretty straightforward. In fact I’m willing to bet my cat that you already do something like this from time to time when learning new words.

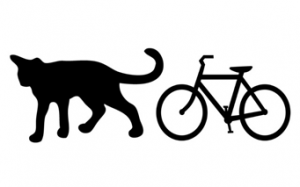

Which image is easier to remember?

I’m guessing you found the second one easier. That’s because when images are combined and are even interacting with each other, they’re easier to remember.

So how does this apply to language teaching? This is where Richard Atkinson steps in.

How it works (and how to teach students to do it)

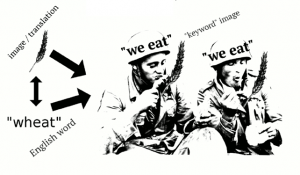

The problem with a lot of students, even the good ones, is that when they learn new words, they tend to simply make a connection between the new word and its meaning (either the translation into L1 or just an image of the word); a two level connection.

What Atkinson proposes is creating a third level, where the new word and its meaning merge to create some sort of potent image.

The procedure for how to do this is fairly simple:

- Take the new word. (In this example, let’s use the word “wheat.”)

- Ask your students to think of what the word sounds like – it could be something in their L1 or something in English. (In this case, we’re going for “we eat” – “wheat” sounds like “we eat.”)

- Create an image! Take a minute or two for this. (In this case, we’re imagining people eating wheat directly — a somewhat unusual image.)

That image – the “keyword image” – will help your students remember the word more quickly.

I see it a bit like a stool. A stool with two legs is rubbish, but add a third leg to it, and you’ve got something solid.

Student examples of keyword images

It’s worth mentioning here, that it’s far better if our students create their own images. They are, after all, the ones who need to remember the words. What’s more, the cognitive exercise itself will give them practice with this useful memory technique.

For some time, I kept a record of the images that my students came up with to create these visual “hooks.” A lot of them were more creative than what I could think of:

pour – sounds like “poor” – Imagine a dinner party with poor servants pouring the drinks.

tangled – sounds like “tango” – Imagine a couple doing the tango getting ridiculously tangled.

smother – sounds like “mother” – Imagine a mother smothering her child.

Bruise – Bruce Willis was constantly covered in bruises, Bruise Willis.

Bloom – Orlando Bloom – Imagine him blooming like a flower.

Fraud – Freud – Freud was a fraud!

This may sound quite intuitive, but it’s surprising how few teachers actually sit down and go through the procedure with their students. When I ask why, I usually get the classic response: “There’s not enough time!” “But this saves time!” I insist. Taking 20 minutes, once, to go through this with your students can really boost their vocabulary acquisition effectively. Yes, once! You only need to do this once, and you’ve given them a valuable tool in the fight against the annoying phenomenon of words just not sticking.

Notes and exceptions

1. Be disgusting!

When creating these visual “hooks,” try to encourage your students to be as gross and as shocking as possible. (They don’t have to tell you the image they’ve created.) The more striking the image, the more likely they’ll remember it.

2. Don’t try to do this for every new piece of vocabulary.

This won’t work for every word and phrase out there. Some words just don’t lend themselves to “hooking.”

3. If you have time, try the following trick to demonstrate the awesome power of the memory.

(It’s also a great party trick you can try with your friends to massively impress them.)

This is called “number hooking,” and here’s how it works:

1. Remember the association of the numbers 1-10 with the following visually striking objects. (They rhyme, so it’s pretty easy):

1 = gun

2 = shoe

3 = tree

4 = door

5 = hive (like a bee hive. So … lots of bees)

6 = stick

7 = heaven

8 = gate

9 = wine

10 = hen

2. Ask your friends to come up with 10 random nouns and tell them you’re going to remember them. Not only that, but you’re going to remember them in sequence. (Make sure they write the nouns down in sequence.)

3. Your friends tell you each noun one by one (in the sequence they’ve written down).

4. Associate each noun they throw at you with its corresponding object above.

So let’s say the first noun is “pirate.” Remember that “one” corresponds to “gun”? Now creating the image is easy – imagine a pirate with a gun.

The next one might be “phone.” OK – “two” corresponds to “shoe,” right? So you can imagine destroying your phone with your shoe.

If seven is “potato,” imagine farming potatoes in the clouds (“seven” = “heaven”). Or potato heaven where all the good potatoes go and hang out with other good potatoes.

Ten might be “salad” – so imagine a hen enjoying a salad. Or bathing in it. You get the idea.

5. When you’ve got to ten, you’ll be amazed that not only can you remember the objects in sequence, but out of sequence, too. Your friend shouts, “seven,” and you come out with, “potato.” Someone else says, “two,” you say, “phone!”

As I said, you’ll need time for this. But if you have it, it can be an effective way of demonstrating to your students how our brain can latch on to images so persuasively, and how to exploit it!

With this new learning tool in their arsenal, they’ll be able to learn English words more quickly, more efficiently and hopefully with some hilariously ridiculous imagery on the way.

1. Bower, G.H. (1972). Mental imagery and associative learning. In L. Gregg (Ed.), Cognition in Learning and Memory, 51-88

2. Atkinson, R., C. (1975). Mnemotechnics in second-language learning. American Psychologist, 3 (8), 821-828