Psychology and ELT: 3 Lessons For Our Field

What can Kobi the Great Teach us?

Case Study – Kobi: The name is Takeru Kobayashi. You haven’t heard of him, have you? This is of course understandable, given that the world of ELT and that of speed-eating contests do not have so much in common. Yet a good teacher is a teacher all the time; she goes around asking herself ‘How did this happen?’; ‘Can I use this?’; ‘Is there a lesson for me here?’. Now I am pretty sure that if this hypothetical teacher came across Kobayashi she would stop and take out her notepad. For Kobayashi (or Kobi for short) is not just an ordinary person; though not quite as well known as Houdini or David Blaine, he is still a living legend…

From poor student to superstar: In the year 2000, Kobi was a 23-year-old economics student who lived with his girlfriend Kumi in a tiny flat. Neither came from a wealthy background and they were in desperate straits. They were behind on the rent and the electricity in the apartment had been cut off as they had not paid the last bill. Knowing that although he was of slight built Kobi had a healthy appetite, Kumi entered him for a TV eating competition.

Kobi was reluctant at first, but he had little to lose, so he set about studying his rivals’ tactics. He would have to outthink them – there was no way he could count on raw ‘eating prowess’. To everyone’s amazement he won. Then he decided to go pro. He set his sights on winning a top international event: the Coney Island hot dog fast-eating contest.

The rules were simple: the contestants were given 12 minutes to eat as many hot dogs and buns (HDBs) as possible. They could add whatever they wanted (though nobody bothered) and they could drink as much as they wanted. It was all about quantity and speed.

At the time (2001) the record stood at an eye-watering 25.125 HDBs – that’s slightly more than 2 HDB per minute (and if you think this is not much, try eating more than three – take as much time as you wish…). What could Kobi do? If he were to have a chance he would have to think and practice. Kobi applied himself to the task.

It is important to start with the right frame of mind, so Kobi started by refusing to even consider the record. It was just a figure. Most people would have used it as a ‘benchmark’ (an ‘anchor’!) but for Kobi it was just what someone had achieved at some point. ‘Impossible is nothing’ as the slogan goes…

When it comes to eating, most people think that there is a simple way of doing things; you take stuff and put it in your mouth. Yet Kobi started without any preconceptions. For instance: it is true that he would have to eat the whole HDB eventually, but there was no rule stating that he would have to do it in the conventional way. The bread and the sausage may taste well together, but they have a different texture and density. The sausage goes down easily; the bun is more of a problem. So Kobi ate them separately.

Another thing is that there was no rule stipulating that he would have to eat the bun as a whole; so Kobi broke it in two. In this way, he got his hands to do some work which otherwise would fall to his (already rather busy!) mouth. Not only that; the bun is full of air, which takes up space. To deal with this, Kobi dunked the bun into a glass of water, squeezed it to reduce the volume and only then ate it (yes, there was no rule against this either!)

This actually killed two birds with one stone. As you eat, you get thirsty, but with the soggy buns he was already getting enough water. Then the thought struck him: why not add a little oil to the water? Then the bun would slide down more easily. So it did – make that three birds…

Kobi experimented endlessly; he measured his performance and kept a record in a spreadsheet. He videotaped his eating sessions looking for inefficiencies and ways of saving milliseconds. He experimented with pace: was it better to start slow and speed up later or do it the other way round (correct answer [a]). He experimented with the water: was it better if it was warm or cold? ([a] again). He also discovered that he could make room in his stomach by doing a kind of jig as he ate (this came to be known as ‘the Kobayashi Shake’).

So, after all this – did he win? Well, I wouldn’t be telling you this story if he hadn’t. Now – what about his performance? Did he manage 28 HDBs? 32? 38? The answer is neither [a] nor [b] nor [c]. Kobayashi wolved down an incredible 50 HDBs! (He also kept on winning for the next 5 years…) (story taken from Levitt & Dubner 2014, pp. 52-61).

Lessons for Educators: What can Kobi teach us?

On the face of it, there is little in this story that could be of any use to us as teachers. And yet there are at least three key elements which are worth bearing in mind:

Redefining the problem: One of the reasons for Kobi’s success was that he started by redefining the problem; instead of asking himself ‘How do I eat more hotdogs?’ he asked a different one ‘How do I make hot dogs easier to eat?’ (Levitt & Dubner 2014 – p. 61). Trying to look at a problem from a different angle has also been used successfully in the past, as the following story illustrates.

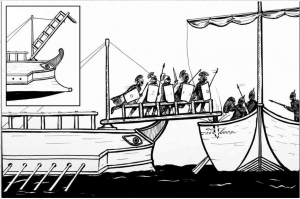

The curvus: During the first Punic war, the Romans found themselves at a disadvantage against the mighty Carthaginian armada. Rome did not have a navy. Having captured one of the enemy ships which had accidentally ran aground, they duly copied it and built themselves a fleet, but copying their rivals’ seamanship would clearly take a long time. The Romans’ strength lay elsewhere: their heavy infantry were far superior to that of the Carthaginians. So the Romans reframed their problem; instead of asking themselves ‘How can we beat our enemies at sea?’ they asked instead ‘How can we play to our strengths?’ Their answer was the ‘curvus’. The curvus was essentially a boarding ramp, fitted with a large spike. When a Roman galleon and an enemy ship got close together, the Romans would drop the curvus, the spike would pierce the enemy deck and the two ships were locked together. Superior seamanship became irrelevant while the Roman skill of close quarter fighting came to its own. The legionaries charged the enemy ships and captured them. Against all expectations, the Romans beat the Carthaginians in their own game! (Goldsworthy 2002, p. 66)

The curvus: During the first Punic war, the Romans found themselves at a disadvantage against the mighty Carthaginian armada. Rome did not have a navy. Having captured one of the enemy ships which had accidentally ran aground, they duly copied it and built themselves a fleet, but copying their rivals’ seamanship would clearly take a long time. The Romans’ strength lay elsewhere: their heavy infantry were far superior to that of the Carthaginians. So the Romans reframed their problem; instead of asking themselves ‘How can we beat our enemies at sea?’ they asked instead ‘How can we play to our strengths?’ Their answer was the ‘curvus’. The curvus was essentially a boarding ramp, fitted with a large spike. When a Roman galleon and an enemy ship got close together, the Romans would drop the curvus, the spike would pierce the enemy deck and the two ships were locked together. Superior seamanship became irrelevant while the Roman skill of close quarter fighting came to its own. The legionaries charged the enemy ships and captured them. Against all expectations, the Romans beat the Carthaginians in their own game! (Goldsworthy 2002, p. 66)

The Moral: For me the takeaway here is this: ‘Are we asking the right questions?’ For instance, should we ask ourselves how to maximize students’ exam results or how to increase long-term retention? Should we focus on how to make our teaching maximally efficient or how to motivate learners so they attend more classes and they make up in quantity what they lose in terms of efficiency? And what about this question: Do people come to our classes because they want to learn English or because they enjoy the feeling of belonging to a group?

Questioning received wisdom: Before Kobi entered his first competition, the world record stood at 25 1/8 HDB. It was generally thought that if someone beat that they would go up to 26 or 27. Yet Kobi refused to accept that as an upper limit since his approach was so much different from the original. Some of the most spectacular achievements in history have been the result of refusing to be constrained by traditional beliefs or practices.

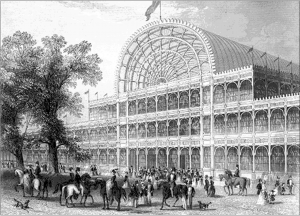

The Crystal Palace: The year: 1850. The place: London. The committee for the organization of the great exhibition of 1851 was facing a problem: they did not have a venue for the event. They needed some kind of building and they did not have it. 245 proposals had been submitted and they had all been rejected. They had a small budget and very little time left. It was clear that nothing could be done. Enter Joseph Paxton. Paxton was not even an architect – he was actually a gardener! Yet he was young and resourceful and he was undaunted by the difficulties. His solution was remarkable: he constructed what was essentially a greenhouse. No bricks, no mortar, no foundations. His construction was essentially a huge glass tent. Taking advantage of the new technology of cast plate glass which enabled the quick and easy manufacture of large, uniform panes of strong glass and using a modular design, Paxton had his plans ready within two weeks. Budgeted at £85,800, his submission was about 2/3 cheaper than the others. The amazing Crystal Palace was ready in 5 months…. (Bryson 2011 – pp. 26-29).

The Moral: The idea here is that it often pays to question received wisdom. Think about ‘truisms’ in our field which have turned out not to be so true after all. Is the use of L1 something to be avoided at all costs in the ELT classroom? Is there no point in trying to teach students more than 7 lexical items in each session? And what about the PPP model or the notion that homework always follows teacher input? (Flipped classroom!)

Testing – testing – testing: A key element in Kobi’s approach was experimentation: He experimented with pace, movement, water temperature etc. He videotaped his training sessions trying to find ways to improve and he kept his data in a spreadsheet (Levitt & Dubner 2014 – p. 59). Talk about professionalism… The same kind of dedicated, obsessive testing and measuring lies behind many a great success.

Sesame Street: ‘Sesame Street’ is a good case in point. Long-running, and hugely successful, this American TV series for children was ground-breaking. But it was not all creativity and inspiration. The producers wanted to make sure that they would be able to hold their young viewers’ attention – and kids’ attention span is notoriously short. So how could the producers make sure that children at home would pay attention? Trying to answer this question, Psychologist Ed Palmer came up with the ‘distracter’. Children were brought into a room, two at a time and asked to watch one of the episodes the team had prepared. Next to the TV screen, there was another screen which ran a slide show. The slides changed every 7.5 seconds and showed all kind of novel things – from rainbows, to weird pictures, to Escher drawings. The question was – would the kids be distracted? Palmer and his assistants would sit through the episode and painstakingly record the little ones’ responses on a chart for hours on end! If they paid attention to the show for about 85 – 90% of the time, this was fine. If the result was around 50%, the episode went back to the drawing board. Respect! (Gladwell 2000 – p. 103).

Sesame Street: ‘Sesame Street’ is a good case in point. Long-running, and hugely successful, this American TV series for children was ground-breaking. But it was not all creativity and inspiration. The producers wanted to make sure that they would be able to hold their young viewers’ attention – and kids’ attention span is notoriously short. So how could the producers make sure that children at home would pay attention? Trying to answer this question, Psychologist Ed Palmer came up with the ‘distracter’. Children were brought into a room, two at a time and asked to watch one of the episodes the team had prepared. Next to the TV screen, there was another screen which ran a slide show. The slides changed every 7.5 seconds and showed all kind of novel things – from rainbows, to weird pictures, to Escher drawings. The question was – would the kids be distracted? Palmer and his assistants would sit through the episode and painstakingly record the little ones’ responses on a chart for hours on end! If they paid attention to the show for about 85 – 90% of the time, this was fine. If the result was around 50%, the episode went back to the drawing board. Respect! (Gladwell 2000 – p. 103).

The Moral: The basic message here is that while a hunch can point us in a certain direction, it’s actual testing that will show us if it’s one we want to follow. For instance: Do speed reading exercises lead to better performance? Gamification might lead to increased motivation, but is this accompanied by better language learning? Is it best for students to follow a rigid study structure set by their tutor, or is a laissez-faire attitude better? The answer is – put it to the test!

Last words – ‘Transference’: In his excellent book ‘Why Don’t Students Like School?’ Cognitive Psychologist Daniel Willingham explores the idea of ‘transference’ (p. 99). The idea is that we often have difficulty using knowledge we already possess because we tend to tag ideas or principles as domain-specific. Yet he argues we could get far greater mileage out what we know and be a lot more creative if we a) look at various situations and compare them b) focus on ‘deep knowledge’ (p. 104). This is why I think cases like that of Kobi are worth studying. …And by this stage I bet you are all dying to see Takeru Kobayashi in action. Here he is (just click here):

[jbox title=”

References:

- Bryson, B. (2011) At Home. London: Black Swan

- Gladwell, M. (2000) The Tipping Point. London: Abacus

- Goldsworthy, A. (2002) Roman Warfare. London: Collins

- Levitt, S. & Dubner, S. (2014) Think Like a Freak. London: Allen Lane

- Willingham, D. (2009) Why Don’t Students Like School?. San Francisco, CA. Jossey-Bass

“]…[/jbox]