The Three Sound Pillars Of A Learning Objective

The biggest mistake a teacher can make is entering the classroom without knowing what he or she is going to teach. That might seem obvious—I certainly hope it does—but I have worked with an alarming number of teachers who don’t take planning seriously. Nevertheless, I am not writing today about those teachers who do not plan, nor am I writing to tell you that you must. I am writing instead about how I approach planning and the three sound pillars of a learning objective.

Entering the classroom without a lesson plan is a foolhardy move, but writing a lesson plan without a clear idea of your targets can be just as problematic. It is important before you start planning that you know clearly what your lesson aims to achieve. This should be more than just, “today I want to talk about x”. A good lesson plan grows from a good learning objective. A good learning objective provides a reference point at all stages of the lesson to make sure that everything you do—every activity, every exercise—is relevant to the target.

Where does a learning objective come from?

A good learning objective should comprise three elements. These three elements are based heavily on a model of competency derived largely from Bloom’s Taxonomy, which is an assessment tool for measuring people’s abilities based on their Knowledge, Skills and Attitude. The idea there is that in order to be considered ‘competent’ in a given field or position, one must possess the necessary knowledge and skills and have the right attitude. If one does possess these three things, then they are a good fit for a given occupation.

Applying this model directly to education programmes requires some minor alterations. I start by switching out the term competency for proficiency. It’s not a widely accepted distinction, and differentiating between the two terms is largely still up for debate with no clear definition in place. However, I consider competency to describe a broad set of traits and abilities required to be able to perform a job, and proficiency the specific traits to be able to perform a certain more narrow/specific task.

That is to say, to be a competent doctor, there are many different things you must know and be capable of spanning all different ranges of ability, but to be, for example, a proficient speaker of English, there are a very tightly related set of performance indicators. Put simply, to be competent for a particular job, one might need to be proficient in many different areas.

With that distinction made, the next step is to very slightly readdress the three components. For competency, it is important that the candidate’s attitude is appropriate so that they fit into the institution or team well and observe and fulfil the vision, mission and objective. For proficiency, attitude is not fundamentally a necessary factor—i.e., one can in theory be a good speaker of English without having a positive attitude towards the language or its speakers. Instead, what I think is required alongside Knowledge and Skills in a model of proficiency is Context.

Context is the ability to apply and combine skills and knowledge appropriately in different ways according to the given situation. It is what makes the language taught in the classroom of real value to the students, because with context, they will be able to actually use the language outside of the classroom.

Developing Your Learning Objective

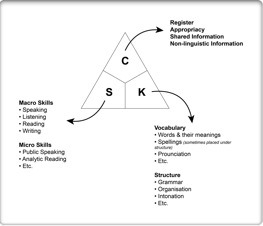

The first thing we must do is identify these three elements within the subject. If we are teaching English, then we need to know what constitutes skills, what constitutes knowledge and what constitutes context. The diagram below demonstrates this breakdown simply.

The first thing we must do is identify these three elements within the subject. If we are teaching English, then we need to know what constitutes skills, what constitutes knowledge and what constitutes context. The diagram below demonstrates this breakdown simply.

While some of the items in the diagram might be up for debate, it illustrates the importance of all three elements. For language (and that goes for any language, not just English) to be learned effectively, it must incorporate all three components. The knowledge is the language elements themselves, the building blocks. Without these, there is nothing to communicate, no message. However, if we have only this component without skill, then we have no way of delivering our message. With knowledge, we simply have a head full of linguistic items but no way of communicating them to other people. Language skills give us the ability to communicate, either by the spoken or the written word. Even so, without an understanding of the contexts relevant to the language, we will not be able to communicate effectively. We might cause offence, or might create misunderstanding.

As such, it is essential that when we teach language, we take into consideration all three elements. This is something we should establish at the very first moment when we start to plan our lesson. Before you choose any materials or activities, be completely clear about what you aim to achieve by the end of the lesson. That aim is the learning objective.

Different institutions provide their teachers with many varied platforms to work from. Some have extremely rigid programmes where every lesson’s learning objective is determined by the institution; some have textbooks for the teacher to follow and adapt; and others have little more than a vague list of topics to be covered. It is the teacher’s job to interpret these programme outlines and identify or develop their learning objectives.

Whether you work for an institution that has a fixed sequence of predetermined learning objectives or you’re a private teacher who chooses yourself what to teach each lesson, always ensure that you have all three proficiency components covered. For example, if you want to teach language related to holidays, it is not enough to say that your learning objective is “language related to holidays”. You need to check for knowledge, skills and context.

Starting with the knowledge component, decide what language element you plan to focus on; is it going to be a vocabulary lesson—in which case you might choose words to describe places or words for holiday activities or words for different types of accommodation—or a structure lesson—in which case you might choose to focus on past tense structures to describe holiday experiences or future structures to discuss holiday plans?

Once you’ve decided on the knowledge component, you need to set a skill focus. Will your students be developing their speaking skill, perhaps by making holiday plans with a friend, or will they be practising their writing skill, maybe by writing a postcard about their holiday activities. Will they be improving their reading skills, for example by comparing hotels and choosing the best one for their needs, or perhaps their listening skills, by hearing some complaints from unsatisfied holidaymakers. Whichever skill you choose—and its possible to combine skills, but more on that in a later article—your lesson should be designed to give maximum opportunity for the students to practise and develop that skill. It doesn’t mean the other skills won’t be used—all lessons make use of all skills holistically—but the skill you choose for your learning objective will be the focus for development.

Finally, you need a context for the language you are teaching. The context is how the language that is learned in the classroom relates to the experiences the students will have outside of the classroom. In this example, the broad context is holidays, and more specifically it could be in conversation with friends or postcards or making/receiving complaints and so on. It is the thing that you expect your students to do with the target language in their real lives.

Applying Your Learning Objective

Once you have identified the three components of proficiency for the language you wish to teach, you should be able to construct a single, clear and focused learning objective to guide you as you plan the lesson. Based on the examples given above, some sample learning objectives could be as follows:

“Students will be able to write postcards describing their holiday activities.”

“Students will be able to make holiday plans with their friends.”

“Students will be able to compare and contrast hotel reviews.”

These are just three simple examples from a potentially very long list. They are also three separate lessons that could all be taught in the same programme at different times, providing good opportunities for practise and recall as well as broadening the application of the target language. However, it is essential that each individual lesson has exactly one clear and focused learning objective. You should not be trying to achieve multiple objectives in the same lesson.

The wording of the learning objective statements above is also important. Opening each learning objective with the phrase, “Students will be able to…” gives the teacher a well defined target for achievement. Once the lesson is over, you can ask yourself very simply, “Well, can they?”. If at the end of the lesson, you can truthfully say, “The students are able to…” then you have met your learning objective. If not, then some remedy is necessary. But more on that in a separate post. These statements are often referred to as “Can-do Statements” because they describe the things your students can do; it is not just a list of words they know, for example.

These can-do statements can also be collected into a list of proficiency markers to compile the syllabus for a programme of learning. If you are provided with a syllabus by your institution, or even if you are given fixed materials to teach from week-by-week, be sure that you analyse the objectives you are given to see that they incorporate all three proficiency components. Often, they will not, and it is your responsibility then to make sure that you add a context, if one is missing, or choose a skill focus, if one has not been determined for you.

Once you have a well defined learning objective in place, you will find that the planning process is much easier and more efficient. Having a clear objective allows you to choose activities and exercises that effectively serve that objective so that every stage of the lesson builds towards your students being able to achieve the aims of the lesson. Planning without a clear objective often results in lessons that lack focus and confuse the students with regard to what they think they are learning. Try it out for yourself and see how much more focused your lessons become.