by Anita Chakrabarti

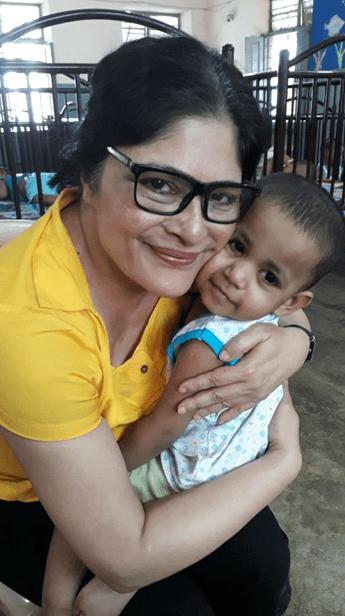

Children from the Avantskill initiative which works towards empowering the underprivileged through English language teaching in India.

English Language was introduced to India in the 1830s during the British Raj. The purpose of introducing English as an official language during the British rule in India was to improve trade and facilitate governance. Furthermore, the introduction of English to the Indian sub-continent served to bring in the western concepts of learning; English medium schools and universities were established, and English became a prerequisite in all public spheres of Indian society.

It has been said that the British Raj encouraged the use of English primarily because of the need to hire more Indians in armed forces and civil services. Moreover, since English was a language adequately known to the Indian elite, the institutionalisation of English as an official language of India helped spread the language across different communities of people in India.

And now, seventy years since Indian Independence, English, the official language of the colonisers continues to be viewed as the most important language in India.

While the spread of English language in India during the Raj formalised a western structure of education, law and order and public sector, it also further aggravated the polarising divide between the Indian elite and the underclasses.

The upper and the middle classes, primarily people of Hindu upper-castes in India had greater access to the English language learning and resources. Therefore, they were successfully able to dominate different industries, public and private sectors, the legal system as well as the educational system.

This relegated a large number of working class people, often from lower-caste and minority communities to the margins of educational and career opportunities. Many Indian people, who spoke in their native languages and dialects, struggled to gain a foothold in a country that modelled itself on the integrated western society and culture.

Any language is an essential part of our culture and in a country as diverse as India, different indigenous languages and dialects are an essential part of the representation of different regions, communities and people.

However, the arrival of English in the Indian sub-continent imposed a language imperialism, forcing Indian people to view English language as superior to their own native languages. Hence, having a command over the English language began to be perceived as being part of the elite and dominant culture of India.

The knowledge of English provided greater privileges to a very small number of Indians, resulting in a gross disparity between the access and resources available to the Indian elite and the Indian underclasses. In other words, the Indian elite thrived using the British masters’ tools and resources and the underclasses continued to struggle to find equal space in Indian societies.

Anita Chakrabarti conducting free English Language class for children from an underprivileged community in Kolkata.

Despite the vast differences in English language knowledge, English serves as a second language in India and not as a foreign language. Needless to say, colonisation of India by the British left its imprint on all Indian people through English language.

Even those with very limited means, such as, most people from lower socioeconomic strata, small towns, rural societies as well as lower-castes, can comprehend and use English in some capacity.

They may not be able to use the language fluently, but they are usually well able to construct basic sentences and use and relate to basic English language structures. However, many learners in India struggle to achieve fluency, command and flair over the English language because of the outdated and archaic methods of teaching.

Often learners are forced to rely more on text-based learning and memorising grammar and vocabulary, hence, they struggle to use the language in context.

Moreover, there is often an attitude that the prior knowledge of the learners is inferior to the knowledge that is being imparted to them through English language teaching.

As English language teachers, we often consciously or unconsciously impose our knowledge, ideologies and culture on non-native learners. We may use symbols and representations readily available to us without accounting for the fact that our learners may not be well-versed with our culture. Moreover, we may forget to consider whether the learner needs to know these cultural symbols and representations at all in order to to learn English.

To cite an example, when teaching a five-year-old child in India, if a teacher uses pictures of fruits such as nectarine, he/she runs the risk of hindering learning because the child cannot relate to that fruit. Also, there is no reason for us to encourage the child to learn about nectarines which are not available in the sub-continent to the masses.

My experience as an English Language teacher for the past nineteen years has taught me that languages are not just learnt through structures but also through feelings, emotions, aptitudes as well as social, economic and cultural factors. Hence, it is critically important that we as teachers make the experience of learning a language an engaging and a relatable one.

We should strive harder to make our teaching more empathetic, where we pay close attention to the personal factors as well as socioeconomic and cultural factors of individual students that may facilitate or hinder their learning.

And, most importantly, we must never consider our learners any less or inferior than us; we must remind ourselves that their prior knowledge and experiences are rich treasures that we can utilise to encourage English language learning. It is not the failure of our learners if they do not learn to use English in their contexts, it is our failure as teachers for not trying hard enough to learn from them.