Mistakes Are Opportunities to Learn

When we’re learning a foreign language, we are bound to make mistakes. As a teacher, I encourage my learners to take risks and praise them when they get out of their comfort zone. As far as I’m concerned, mistakes are learning opportunities.

“To correct or not to correct at all?”, asks Philip Kerr

I say correct. Definitely. Why? It’s part of the service which we’re offering our learners. The way I see it, if we don’t give feedback on language, we’re just being polite listeners. When I pay for a language course, I certainly expect the teacher to correct me.

The way we choose to do it will make a difference, though. It’s all about finding the right time, the right technique, the right tone of voice, etc. Doesn’t sound very easy, does it? Read more about giving feedback on speaking here

Errors or mistakes?

Then, we also have different types of inaccuracies. Errors, mistakes… Is there a difference? Some writers use these terms interchangeably; others mention they’re different. I like these two definitions:

Errors are new mistakes. Students don’t’ know the form, so they are experimenting. (TeachingEnglish | British Council | BBC, 2008)

Mistakes are inaccuracies caused by anxiety, tiredness, or other reasons. Students know the correct form but don’t produce it. If prompted, they’re able to correct their mistake. (Swift, 2010)

Persistent mistakes

As you might have noticed, even though you correct the same mistake over and over again, students might still repeat it. Here are some examples which I’m sure you’ll recognize:

| Omitting the third person -s, e.g., he play football. Mispronouncing vegetables, e.g.,/veʤeˈteɪbəlz/ Using adjectives after nouns, e.g., a hat red. |

Don’t let them become part of their interlanguage

So, although I believe that errors are a vital part of the learning process, I think repeating old mistakes is a setback. It deserves more attention. Sure, they might not impede communication, but not trying to “fix” them might lead to fossilization, or stabilization, i.e.: a process which sometimes occurs in which linguistic features become a permanent part of the way a person speaks or writes a language. (Richards and Schmidt, 2002)

Let’s have a look at some ideas on how to draw your learners’ attention to common mistakes and hopefully eradicate them.

First of all-record them

This is the most important step. Write down examples of incorrect sentences produced by your students. Keep one list per class. Then, use said list occasionally to remind learners of the correct form or pronunciation at the beginning or end of class. You’ll notice that you’ll be updating it by adding or removing items during the year. How can you use this list?

1. Kahoot them

Create a Kahoot quiz for your students. They all love Kahoot, so it’s a fun and quick way to get their attention and make them reflect on their mistakes. Use it as a back-up activity now and then.

2. Whiteboard race

Write those incorrect words/sentences on a sheet of paper and place it on the whiteboard. Run a race; students work in groups; one person from each group at a time can correct one sentence, then pass the marker to their teammate to correct the next sentence. Use it as a warmer or cooler.

3. Reverse translation (YouTube, 2016)

First part: tell them you’re going to dictate some sentences, and they have to translate them directly into L1. Don’t show them the sentences. Include language they would generally misuse. When they finish translating them, tell them to put this sheet aside and go on with the lesson.

Second part: A bit before the end of class, tell learners to find that sheet and translate the sentences back to English. Reveal displayed sentences on the whiteboard. Learners notice their mistakes, and as Thornbury (2014) says, they are triggered to fill this gap.

Reverse translation suits monolingual groups, as learners, can compare and reflect on their sentences together. It also suits multilingual groups, as learners become teachers at the end of the activity when they see their own mistakes; the teacher does not need to speak the L1. See example below:

| English | He must be crazy |

| Translate to Spanish | El debe estar loco |

| Translate back to English | He must to be crazy |

| Notice error | He must |

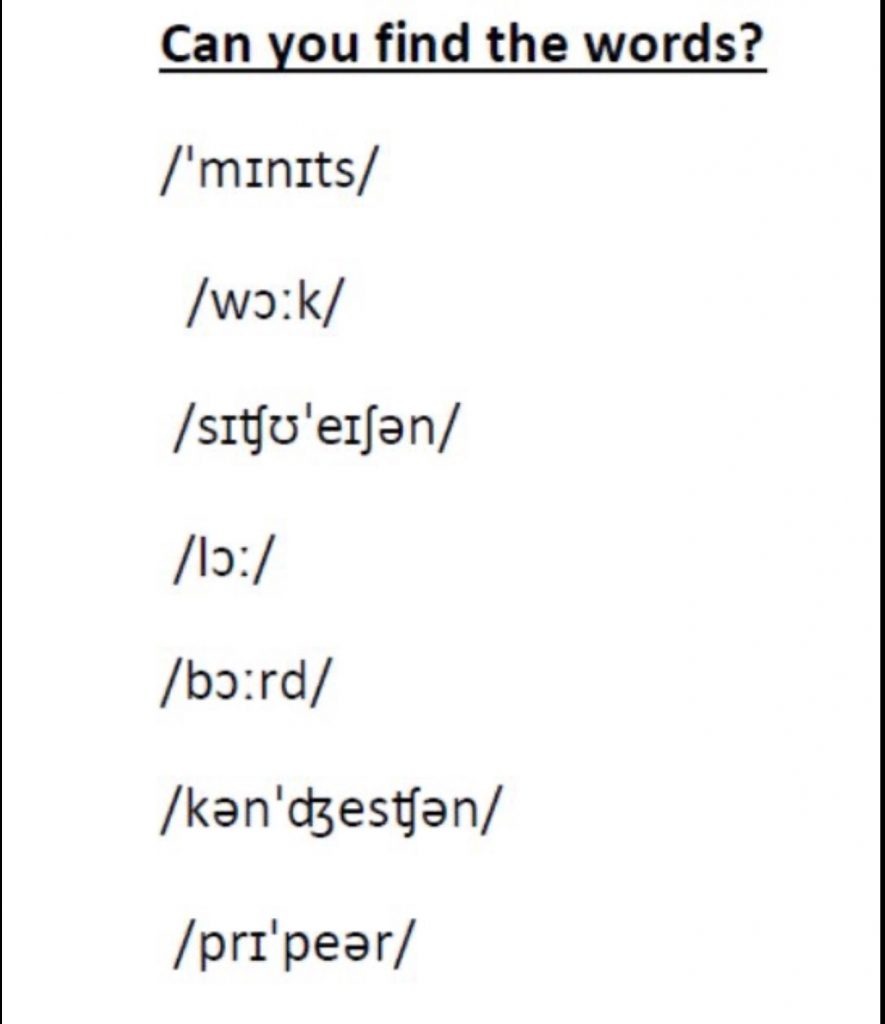

4. Write the phonemic script and elicit the word

I’m one of those teachers who believes the phonemic script is an incredibly useful tool. I always train my learners to use it, and it seems to help them improve their pronunciation.

For instance, most Spanish learners say /ˈmɪnʊts/ instead of /ˈmɪnɪts/. So after correcting them, I also note it down as a common pronunciation mistake. Then, in the next classes, I project a list like the one below and ask them to find the words.

Differentiation

With teens, I make it more competitive and set a time limit or give them points for right answers. They find that very exciting, as it’s like decoding a message!

I’ve been using these activities for a few months and noticed that my students are slowly getting rid of a good number of mistakes. What about you? Do you use any of these activities? If not, would you?

References:

- Kerr, P. (2017). Giving feedback on speaking. Part of the Cambridge Papers in the ELT series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Richards, J., and Schmidt, R. (2002). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics.

- Swift, S. (2010). An ELT Glossary : Mistakes. [online] Eltnotebook.blogspot.com. Available at: https://eltnotebook.blogspot.com/2010/11/an-elt-glossary-mistakes.html [Accessed 29 Feb. 2020].

- TeachingEnglish | British Council | BBC. (2008). Error Correction. [online] Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/error-correction [Accessed 27 Feb. 2020].

- YouTube. (2016). Philip Kerr: The Return of Translation. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kk-DUsgaZ4o [Accessed 3 Mar. 2020]