By Sharyn Collins

Elizabeth, you continue to have an extraordinary and fascinating life, could you tell me where it all began?

I was born in 1952 in Budapest. My sister 17 months later. Although our parents were very happy about starting a family, both my sister and I belonged to the so-called ‘Ratkó children’, named after the Minister of Health, Anna Ratkó, who banned abortions. Less than a decade after World War 2 and only a few years after one-party socialism had been established in Hungary, the country needed a new generation to build the socialist state.

What did your parents do in Hungary?

My parents had worked as young journalists, but after the 1956 revolution (an uprising against the socialist political system) was crushed by the Soviet army, my mother became a secretary in an industrial company. My father was assigned to a semi-skilled job in a factory producing the famous Ikarus buses.

Later he became a successful writer and worked for the Hungarian State Television. Many years before America’s Got Talent started, he put on talents shows for young people (Ki Mit Tud – “Who knows what?”). On the days when the programme was broadcast, the streets were deserted and neighbours gathered around the one and only TV set that a slightly better off family may have bought on hire-purchase.

After my parents divorced, we went to live in Budapest with my mother and new stepfather, who was a faithful cadre of the party. Since many diplomats and embassy personnel did not return to Hungary after the 1956 uprising (and about 200 thousand mainly young, talented professional people crossed the border into Austria to flee the reprisals), those who stayed were moving fast up the ladders of upward mobility. By then my stepfather was trained as a technical engineer and was sent to take English classes. He started making business trips and we marvelled at the chocolates and nylon stockings that he brought back as presents.

One evening, it must have been 1963, he came home and asked my mother: “Where would you like to go on an assignment? Japan or India?” “India, of course” replied my melodramatic mother, who loved opera and poetry and read the books of a 19th century Hungarian ethnographer who had travelled widely on the subcontinent.

Where did you do your schooling?

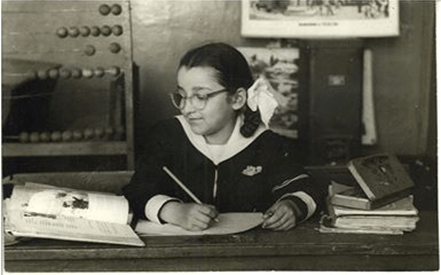

I spent two years in India and then came back to Hungary to start my secondary schooling in a famous boarding school in Buda, which was nationalized, but still had brilliant teachers from another era. I loved my Latin teacher and was preparing to become a doctor. During the third year of high school, my sister and I went back to India for my parents’ final year there. At a party for embassy kids, I got to know a Farsi-speaking Iranian boy, who was also going to study medicine. We started talking and my English began to improve by leaps and bounds.

I understand that at university you didn’t tow the party line.

I changed my mind about becoming a doctor and majored in English and History instead. At university I got involved in the student movement; we held make up classes for disadvantaged Roma teenagers and fought the officials of the one-party youth movement tooth and nail. I married one of the opposition student leaders and started working at the College for Foreign Trade teaching general and business English.

My daughter was born and we moved out of Budapest, because we decided to set up a clandestine printing press at our house. For a couple of years, every second month we printed 1200 copies of a stencilled samizdat journal that described the malfunctioning of the command economy, the poverty of the Roma, the widespread corruption of the ruling elite, the oppression that the Hungarian minority suffered in Slovakia and Romania – issues that had been swept under the carpet for decades. The badly printed, smudged copies were distributed by a network of like-minded people and reached a huge readership. Once I was offered a copy to read by a colleague at work – he had no idea.

But the police must have, because they came looking for my husband. They didn’t have a search warrant, so I talked to them outside the house while my husband left through the back garden with the stencil machine. We were worried they would come back, so we burnt as much of the current copies as we could and no, you cannot remove stencil ink from the carpet.

How did you come to live in England?

By this time my daughter, Agi, started primary school. One day the teacher asked the kids what their parents did. “My dad is a plumber,” said one. “My mum is a nurse,” said the other. “My parents are making books at home,” said my proud daughter. We knew we had to stop.

That summer we left Hungary holding tourist visas, applied to George Soros’ Open Society Foundation for a scholarship and stayed in the UK for a year, where I did my Masters on cross-cultural communication at Exeter University. We rented a tiny house in a village called Ide where my daughter started going to school. “My jumper,” she said to her teacher on her third day during break time, asking her to hold her cardigan. By December she was fluent.

You returned to Hungary, but were you welcomed with open arms?

Not exactly. When we arrived, my husband’s passport was confiscated, because he had published some anti-government articles while we were in Britain. I had no job to go back to because of having accepted the scholarship without the approval of the Education Ministry.

It was at this time that my husband was diagnosed with cancer. The future in Hungary looked bleak and we quickly realized that we had to leave once more. One of the opposition leaders went to the British Embassy to arrange for us to leave the country. That was by no means easy in a socialist country and it took months of negotiations behind the curtains.

I understand that Margaret Thatcher helped you? Could you explain how?

That spring the British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher came to visit Hungary. As was usual in those years, each Western leader used to have a folder with a couple of human rights cases when they visited a socialist country and fortunately that year we were the case!

A few weeks later my husband was given a one way permit to leave the country and Agi and I were given consular passports. When we landed in London the Immigration Officer asked to see our return tickets. We told him we didn’t have any and he asked us to wait. When he came back he shook our hands; he had never seen anyone granted political asylum on the spot…

How did you come to work for the BBC?

The BBC’s Hungarian Section was a wonderful mix of longtime and freshly arrived refugees and dissidents and anything else in between. I started doing ad hoc shifts and later I was made permanent. Eventually I was promoted to senior producer. I wasn’t a good journalist, but I was a good “human interest stories” feature writer and broadcaster. I also turned out hundreds of bilingualised English by Radio materials. To this day I believe that broadcasting and teaching is the same: you talk about important things in an interesting fashion.

Finally you became an EFL teacher

My beloved Latin teacher always said, “All you need to turn this country around is 3000 good teachers.” She’s right, I thought to myself. When you’re a doctor, you treat sick people, when you’re a teacher you’re treating the psyche of a whole nation.

English was the obvious choice with my school years in India, (unlike my daughter, I have never fully mastered the language and after teaching it for more than 40 years, I’m still a non-native speaker). However, one thing I may have acquired is stress timing. I tend to speak and write in a stress timed manner, a lovely feature of the English language.

When I left university I taught English left, right and centre. In the small village where the underground press was set up, there were only three kinds of people: those I had taught before, those who were my students right at that time, and those who were lined up to become my students in the future. I taught general English, business English, did translation and interpretation.

So could you tell me how you have ended up in Ecuador?

I worked for about 17 years in the Hungarian Section of the BBC’s World Service but I missed teaching. So finally I took early retirement and went to live in Crete where I worked as a volunteer teacher giving English classes to North African, Albanian, Russian and Ukrainian immigrants.

I bought a small house in Rethymno. My daughter had just finished her second Masters at the university there (defending her thesis on ‘free will’ in Modern Greek) and she told me that she was going to look for a job as far from Europe as possible, because when she got married, she wouldn’t be able to travel far. She got a job as Director of Studies in Cuenca, Ecuador, and a year later got married to her husband, who worked as systems engineer at the same language school.

I visited them as often as I could, but I also felt that I had a window of opportunity that would never return, so I signed up with Voluntary Service Overseas and went on an assignment in Ethiopia for two and a half years. By the time I got back, the global property market had collapsed, but I was still able to sell my house in Crete and buy one next to my daughter and son-in-law in Ecuador.

I love Ecuador and especially Cuenca, the country’s cultural capital. The people are direct and open-hearted, quite close in emotional makeup to Hungarians and Cretan Greeks. The climate is lovely and the natural beauty of the mountains and the seaside is quite spectacular.

Of course, I’ve never stopped volunteering. I have taught English to members of an indigenous tribe called the Achuar in the Amazonian region. After spending almost six months in a jungle school, I now do volunteer shifts in a day care centre near Cuenca for disadvantaged children. I still take on a lot of language-related work, act as thesis supervisor, and mentor young English teachers in their research and publishing projects.

And things are going full circle in my life. My daughter and I are going to India for Christmas, and unless there is a health reason not to, in 2019 I will volunteer at Shanti Bhavan* school in Bangalore for three months.

It is a residential school for the poorest of the poor: the untouchables. After about 17 years of training and education the students there gain more than just first-class education. They become self-confident, reflective young people with one more essential ingredient: dignity.**

*See “Daughters of Destiny” 4-part documentary series on Netflix

** TED talk on Shanti Bhavan by the school founder’s son, Ajit George

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYB5qgWcbSs