Teaching Collocations – Best Approaches for Success

Teaching vocabulary in the ESL/EFL classroom can sometimes excite or it can sometimes frustrate teachers. In the scope of vocabulary learning, are there ways to help our students acquire language efficiently and guide them toward the useful real-world language that we native-English speakers use so effortlessly? Let’s take a closer look.

What is collocation?

In English, there are words that co-occur frequently, for example, a ripe banana, a cute puppy, and a long road. These are collocations. In addition to nouns and adjectives, we can find noun + verb collocations such as the lion roared (not barked), the stars twinkled (not shone), or verb + noun combinations such as, He’s picking strawberries and I’ll take my coffee with cream and sugar. There are also noun + present participle collocations in compounds, such as train-spotting and bird-watching.

Collocations are wonderful chunks of language that native speakers of English use naturally and frequently. As teachers, it is our responsibility to show our students ways in which they not only understand meaning of these special language groupings, but ensure that they use them in the appropriate contexts.

Why are collocations important in language learning?

Collocations are extremely useful for the language learner to be aware of and begin using when developing their second language. English-native speakers are already aware of which verbs co-occur with particular nouns, which adjectives frequently latch on to certain nouns, and frequent and current idioms. Examples include stand down, get over, and catch phrases such as, keep smiling and chin up. An advantage of teaching collocations in the language classroom can assist learners with fluency. According to James Nattinger, a renowned linguisitics professor at Portland State University, instruction of chunks of language helps learners avoid incongruity. To understand collocations further, lets have a look at the various kinds.

English for Specific Purposes PDF

Types of collocations

There are four types of collocations:

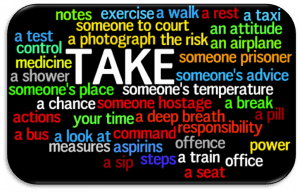

Type 1: De-lexicalized verbs

These kinds of verbs, for example, get, have, do, take, put, are very important when teaching collocation because they have a basic meaning (make = create/manufacture, have = own/possess), and they are more commonly used in combination with other nouns as a chunk of meaning:

| make a mistake | do your homework | take an exam |

It’s quite common for language learners to struggle with de-lexicalized verbs due to first-language interference, i.e. learners translate words from their first language directly, or they simply guess which verbs go with particular actions. For instance, some de-lexicalized words such as “make” and “do” have the same meaning in the learner’s mother tongue, and this leads to many incorrect collocations, such as “make homework” instead of “do homework” or “do mistakes” instead of “make mistakes”.

Type 2: Nouns

It is quite useful teaching learners collocations with a noun as key word because the majority of general nouns usually require further qualification:

| Adjective | Noun | Adjective | Noun |

| good | package | ||

| well-paid | luxury | ||

| menial | expensive | ||

| boring | job | cheap | holiday |

| full-time | good | ||

| part-time | terrible | ||

| sought-after | exciting |

Nouns are also important because they are usually the words that carry the most meaning within a sentence.

Type 3: Strong/Weak and Frequent/Infrequent

A frequent collocation (e.g. a warm day) is not necessarily strong, as either word in the partnership suggests a number of other collocates:

| sweater | sunny | ||

| blanket | wedding | ||

| (a) warm | smile | (a) bad | day |

| hug | rainy | ||

| breeze | glorious |

Similarly, a particularly strong collocation may be used very infrequently (e.g. bat your eyelashes). The most useful combination for teaching purposes seems to be a combination of strong (but not completely fixed) and frequent. It may be worth mentioning strong/infrequent and weak/infrequent collocations to draw students’ attention to their existence or possibly for interest. Teachers do not really need to devote too much time to discussing them.

Type 4: Idioms and Phrasal Verbs

English is heavily loaded with a vast array of idioms and phrasal verbs for learners to enjoy (and struggle with). Michael Lewis, one of the most influential linguists specializing in lexis who is most known for his work, The Lexis Approach (1993), asserts that it would not be wrong if we claim that all collocations are idiomatic and all phrasal verbs and idioms are collocations or contain collocations. In other words, we can view collocations as one giant umbrella covering various lexical groups. The table below gives some common idiomatic expressions:

| cream of the crop | take one for the team |

| He’s giving me the eye | For the presentation tomorrow, you’d better knock it out of the park. |

How you can implement collocations in the classroom.

So, what can you do with all of this information? Let’s get down to the nitty-gritty and examine an instance on how you can incorporate collocations into your lesson plans.

John Sinclair (1991) gives a good instance of a pre-constructed phrase that speakers choose instead of choosing individual words. The phrase of course operates as effectively as a single word, Sinclair says, and “we are dealing with a fairly trivial mismatch between the writing system and the grammar” (p. 110). Specifically, of in this phrase is not the preposition we find explained in traditional grammar books. Furthermore, course is not the countable noun that Oxford or Merriam-Webster dictionaries put forth; its meaning is not the property of the word, but of the phrase. Therefore, to use it in way that fulfills its definition, i.e. if it were a countable noun in the singular, it would have to be preceded by determiner to be grammatical.

In noting this information, it is reasonable to put forth that teachers should not teach of course as individual items, but rather as the collocate it is. For example, teachers can use synonyms such as definitely, obviously, or absolutely to replace of course depending on the context. Learners will then understand the collocation in this light, rather than a preposition not used in its traditional fashion linked to a countable noun that here actually is not countable. Does that make sense? Of course!

Collocations Activity – Scavenger Hunt

How much time should you spend teaching collocations?

This is a challenging question. Answers may suggest that every teacher is different, every class is different, and the contexts of classes are different. How much time do you actually have in the lesson to discuss the various collocates of run, take, and the time you flipped your wig?

Paul Nation is a leading language and teaching methodology and vocabulary acquisition researcher. He makes the point that, in a classroom situation, frequent collocations only deserve attention if their frequency is equal to or higher than other high-frequency words. In other words, focus on phrasal verbs, expressions, and idioms that are used in real world English most frequently, and don’t overwhelm yourself. This puts a greater pressure on the teacher when making the decision about whether to spend time on a particular collocation. If there are enough potential frequent collocations of one of the nodes, it is worth spending some class time on:

| take a | |

| put (yourself) at | risk |

| run the |

With the second two verbs in the above example, the unpredictability of the combination is also a factor. Most learners at intermediate level or above would be familiar with all three of the verbs, but few would realize that it is possible to collocate ‘run’ and ‘risk’. Moreover, this would be a difficult collocation for learners to work out just by knowing the meaning of the individual parts, so would therefore merit some class time.

If you would like to exercise your inner-nerd, er, inner-linguistic Viking, then you could take some time and explore an English corpus to find generated lists of frequently used collocations. I suggest COBUILD to start (Collins Birmingham University International Language Database) where you can insert the words you would like to find the collocates for. For those who are slightly less adventurous, there are copious amounts of collocate lists to be found in traditional and online resources.

Now that we have seen how collocations benefit from being taught in the classroom, let’s examine some potential challenges teachers may encounter.

The Lexical Approach – A Beginners Guide

Challenges

Despite the benefits and usefulness of collocations for learners, learning how to produce them is actually quite challenging. An idiom such as, in a nutshell, carries very subtle nuances in meaning that learners need to be aware of. Specifically, learners need to understand what the shell of a nut is, and furthermore, how this expression actually has nothing to do with nuts whatsoever. However, they should be made aware that the shape of the nut is typically round or a shape that has no points or ends sticking out, symbolizing a whole. Additionally, nuts are typically small in size, which is comparable to saying something in brief, or giving a summary of an event. Therefore, in a nutshell is a clean, complete, and brief way to describe an occurrence, for example:

A: How was your trip?

B: Well, in a nutshell, it was fantastic!

Additionally, students need to develop preferences, and make word choices, which they feel are appropriate. Idioms tend to create excitement among learners as they develop their language proficiency, and thus the teacher may need to guide them towards the most useful ones. Consequently, teachers need to properly assess idioms carefully beforehand in order to decide which ones to use in the classroom.

How to Teach Collocations – The Sure-Fire Way

Suggestions for overcoming these challenges

When English teachers are with their students in the classroom, they have extraordinary opportunities to expose learners to useful language, functions, and vocabulary in interesting and exciting contexts. In keeping with their curriculum, teachers need to choose which structural and functional knowledge to work with and which to abandon. When deciding on which collocations to introduce, teachers may be a little overwhelmed with this potentially daunting task.

Let’s look at some specific examples.

Based on what I have read and observed, both in my own learning and teaching experience of English, I can say learning collocations might be quite challenging for most learners. Even words such as “big”, “large” and “great” could be tricky. Take, for example, the phrase “a great deal”, which means “a lot”. A near equivalent would be “a good deal”, but if we say “a big deal”, the meaning changes. Moreover, “a large deal” is quite unlikely to occur at all. Consequently, taking into consideration that there are many more collocations than words, as many words occur in several different collocations, it is quite understandable why our students, especially at lower levels, fail to produce “natural” sentences most of the time. Below you will find more reasons why students encounter problems while using collocations:

- The same collocation sometimes does not exist in the same form.E.g.: Some Turkish students tend to say “to be friend with” rather than “to make friends with”

- Some learners might over-generalize some structures and make mistakes.E.g.: As “beautiful” is common and may collocate with many nouns such as “woman”, “child”, “day” etc. students tend to say “beautiful man”.

- Learners sometimes may translate word-for-word rather than chunk-for-chunk, which leads to collocational mistakes.E.g.: “ski station” for “ski resort” (A mistake made by a French student who translated the phrase “station de ski” word for word)

As teachers, to help our students overcome the above-mentioned problems we need to design instruction to focus on what they need. That is, our instruction should help learners avoid incongruity while assisting their fluency in production. At this point, it would be useful to present the rationale and activities that incorporate teaching collocation into our lessons, all designed to help our students develop collocational competence. (i.e. the skill to select, store and retrieve chunks).

Collocations Lesson – How to Teach

Collocations are a fantastic way to bring the excitement of vocabulary building into your classroom. They help your students acquire real-world or academic expressions by helping them learn language in chunks, rather than individual words. Collocations also encourage students to focus on meaning and context, rather than memorizing endless lists of words and their strict definitions. Encourage your learners a little differently by helping them see the world not as individual bits, but as groups of information rich in nuance and understanding.

Hedge,T. (2000). Teaching and Learning in the language classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, M. 2000. Teaching collocations. London: Language Teaching Publications.

Nation, I.S.P. (2000). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language.

Nattinger, James R. and Jeanette S. DeCarrico. (1992). Lexical Phrases and Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2 Responses

Ekaterina Zubkova

It is important to learn and teach collocations. Unfortunately, there are not so many books on collocations of Types 1-3. So I have to select them very carefully or create my own materials. It is exciting but takes time :)

30/11/2015

Olga Frecautan Rotari

May I know the nr of volum and pages of this arcticle in Journal?

08/01/2018