Teach Phrasal Verbs – The Global Approach

Teachers and learners tend to perceive Phrasal Verbs as difficult to learn, particularly as they seem to have so many alternative meanings, yet they are among the first verbs acquired by native speaker children. You’ve probably encountered them in traditional lists as discrete items of vocabulary, often paired with their Latin cognates, e.g. come back / return, as a massive load to be learnt by heart. Happily, there is a much better solution, requiring a complete shift in approach. As with every component of any language, you have to think ‘system’.

To give you a little background: my husband and I have been running a small residential language centre for over thirty years, during which time we’ve also raised four children. My youngest child aged four, was playing with a toy car when a student teased him by grabbing it and putting it behind his back. My son protested with ‘Oi, give me back my car; give me my car back’. The student asked, ‘how does he know that ‘give back’ is a separable verb?’

On another occasion I asked my ten year old daughter what the difference between ‘return’ and ‘come back’ was. Her response was immediate: ‘return’ is a grown up word and ‘come back’ is a children’s word.

In principle she was right. The mark of an ‘educated’ native speaker of English is the volume of Latinate vocabulary he or she possesses. Children start with the Germanic register, which is where phrasal verb belong. Latinate vocabulary features particularly in formal speech, especially in disciplines such as law and medicine, whereas Germanic vocabulary features highly in informal speech.

This has a historic parallel. Following the departure of the Romans and the arrival of the Anglo Saxons in Britain in the fourth century, a form of German became established as the lingua franca. This was reinforced by the arrival of the Vikings in the eighth century. The Celtic languages were pushed to the west of the country. Some Romano British families survived so that Latin remained as an administrative medium reinforced by its use in monasteries. Following the Norman invasion in 1066, French, derived from Latin, was established as the colonial language. English retains this Germanic and Latinate duality.

Latin vocabulary includes specific words for both concrete and abstract concepts. By contrast, the key to understanding the system of phrasal verbs – and it IS a system – is to understand that concrete concepts are used METAPHORICALLY and SYMBOLICALLY to communicate abstract concepts. If I ‘look up’ a tree, I’m doing something physical, so ‘up’ in this context has a primary, literal meaning and is a preposition; I can’t change the order to ‘I look a tree up’. However I can ‘look up something in a dictionary, or look something up’.

Here ‘up’ takes on a secondary or symbolic meaning and becomes a ‘particle’ as the component of a phrasal verb. (In a dictionary we usually start by looking at the guide word at the top of the page: i.e. we ‘look up’). For this reason, phrasal verb only have ‘meaning’ in CONTEXT. It’s pointless trying to translate them in a one-to-one correspondence. A phrasal verb has as many ‘meanings’ as the contexts in which it can be used. So, the definitions listed in dictionaries are interpretations of possible contexts, not translations of meanings.

The good news is that phrasal verbs are one of the easiest aspects of English, provided you can get your students to make the necessary mind shift. Unlike Latinate vocabulary, as components of a flexible system, they can be GENERATED. It is thanks to their potential ambiguity that they can be used so creatively, forming much of the basis of English humour.

Teach Phrasal Verbs: How To Present The System

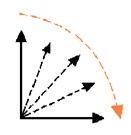

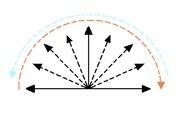

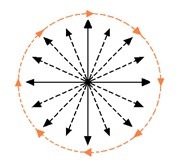

Start by examining the core concepts. The ‘meaning’ is not in the ‘verb’ part of a phrasal verb; it is in the ‘particle’. The most frequently used particles are few in number, and are derived from prepositions and adverbs of MOVEMENT. Movement is VISUAL. So the key to understanding phrasal verb is to approach them visually and kinaesthetically, from the simple perspective of a young child.

Let’s start with the particle ‘OVER’.

Get your students to gesture or draw what they understand this to mean.

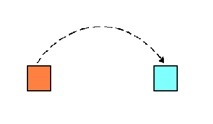

You’ll probably get something like this: (Over is spatially a vertical concept).

Now ask them what this could symbolize. For example, it could indicate ‘from one side to another’. The next step is to explore what contexts you could apply this concept to.

Here are some ideas. Get your students to gesture these movements.

|

|

|

|

| transfer | vertical to horizontal | reflection | repetition |

| (he handed over the microphone) | (she tripped over the carpet) | (we need time to think it over | (she explained over and over again) |

|

|

||

| surplus | |||

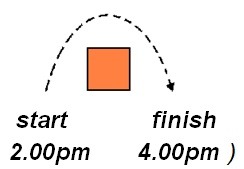

| (the meeting started at 2:00pm and was over by 4:00pm) | (the beer spilled over the rim of the glass) |

_________________________________________________________________________

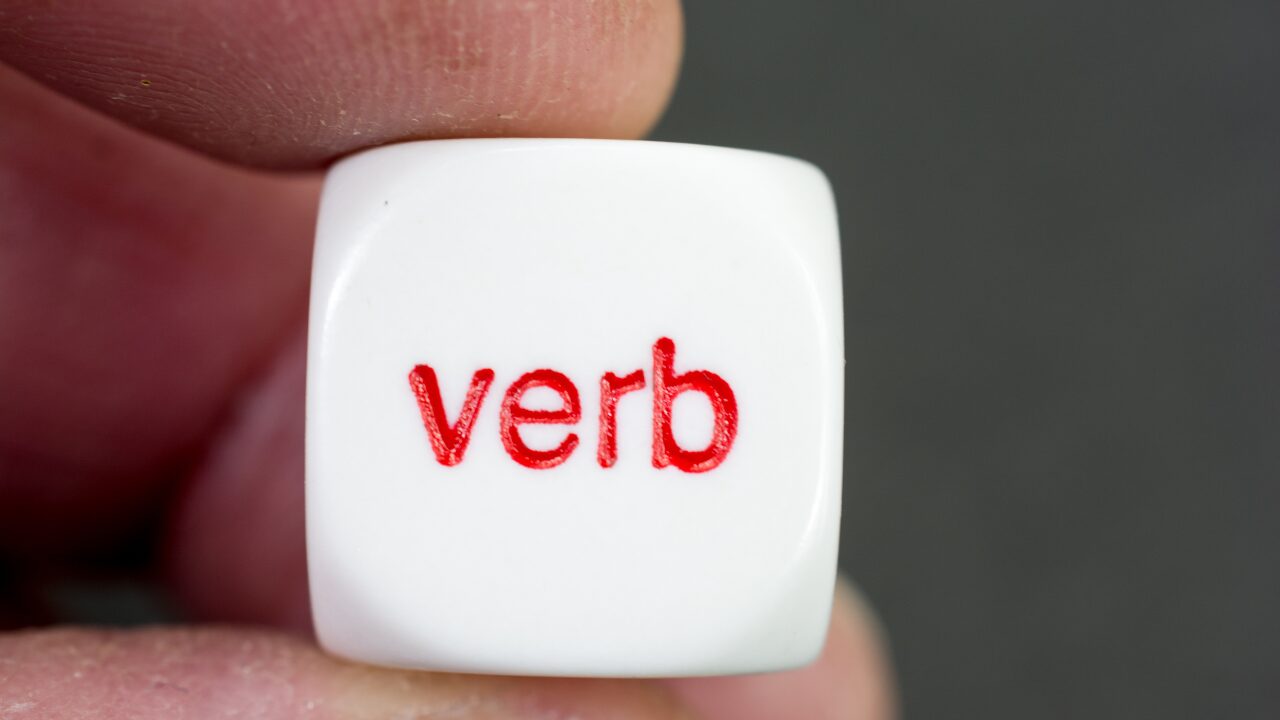

GET

I mentioned earlier that the particle contains more meaning than the verb. This is particularly true with ‘GET’. If you look in a dictionary you’ll see pages of ‘get’. That’s because ‘get’ itself has no lexical meaning. It is like a passe-partout, skeleton key or ‘joker’; it can mean more or less anything you want it to mean. Sometimes I demonstrate this in teaching by substituting the word ‘verb’ or a clap, or any other noise in place of ‘get’.

For example:

‘On weekday mornings I usually (verb) up at 6.30a.m. I (verb) dressed, (verb) myself a cup of coffee and a bowl of cereal and (verb) the children ready for school. I (verb) into my car at 7.30 and (verb) into my office at around 8.00. I (verb) a lot of emails and phone calls during the day. In fact I (verb) a bit irritated with all these emails. Some of them seem so unnecessary. By lunchtime I find I’m (verbing) a bit weary, so I (verb) my coat on and go for a short work.

There are some shops nearby, so I often (verb) a little treat for supper. I (verb) home in time to (verb) the evening meal ready. After supper I chase the children to (verb) their homework done, and then it’s usually a battle to (verb) them to bed. I try to (verb) some reading done myself before it (verbs) too late. I like to (verb) about eight hours’ sleep a night if I can.’

Of course, the overuse of ‘get’ is considered to be poor style, precisely because it is so non-specific.

Of course, the overuse of ‘get’ is considered to be poor style, precisely because it is so non-specific. It has a grammatical function, serving as a bridge between subject and object (or complement) and little else. The sense being in the context, if you were translating the passage above into another language, you would need to find specific verbs to communicate meanings that are only implied in English.

Try this out

Now try this exercise with your students: either you or one of them stands on a chair. The rest of the class calls out instructions: ‘get down from it, get off it, get round it, get under it, get over it etc. Notice that the spoken stress is always on the particle, because that is what communicates the meaning.

With a chair we are focusing on a concrete object, but we can extend this to abstract ideas. For example, you can ‘get over’ an illness or shock; when money is tight you can manage to get by; you might have to get round a problem, or through a rough patch. These are all embedded metaphors.

_________________________________________________________________________

Other commonly used particles are ‘UP’ and ‘DOWN’. Let’s look at some of the many interpretations frequently associated with them. Again, ask your students to gesture their understanding of these concepts, and then get them to think how they can be used symbolically.

Possible interpretations of ‘up’ … Possible interpretations of ‘down’ …

- Approval (thumbs up) Disapproval (thumbs down)

- Upward direction (fly up) Downward direction (fall down)

3) Construction (put up) Demolition (pull down)

4) Vomit (throw up) Swallow with resistance (drink down)

5) Establish (set up)

Clean with water (wash down)

Record on paper (write down)

Fail (break down)

Some phrasal verbs are derived from historical metaphors, e.g. a rider would literally ‘pull up’ the reins to make a horse go slower or stop, and pull the reins over, to make it move to one side.

_________________________________________________________________________

‘Up’ and ‘down’ can also indicate INCREASE and DECREASE …

fatten up / slim down; go up in price/ go down in price; speed up/slow down; heat up / cool down; cheer up / calm down; turn up / turn down; harden up / water down

___________________________________________________________________

If you think of a fairground competition where the winner has to send the weight all the way up to the top to ring a bell, you can see how ‘UP’ can indicate COMPLETELY.

Examples include what the barman in an English pub traditionally used to call out just before closing time – meaning ‘finish your drinks’: ‘time gentlemen, time; drink up please!’ (If you empty a beer glass you also up-end it).

The shed is locked up (completely locked); they smashed everything up (smashed everything completely); they tidied up after the party (tidied completely); the crowd broke up into little groups (the original crowd fragmented completely).

_________________________________________________________________________

A further interpretation of ‘up’ is the idea of IMAGINATION of CREATIVITY. If you’ve ever worked with NLP you will know that raising our eyes, particularly to the right, is an indication that we are visualizing something imagined. This is reflected in English with expressions such as, ‘How did you think/dream/ cook that up?

_________________________________________________________________________

UNEXPECTED OCCURRENCE is yet another possible interpretation of ‘up’. e.g. ‘I’m sorry but I’ll be home late; something has just cropped up in the office, so I’m having to stay behind.’

_________________________________________________________________________

As a final example, let me refer you to the idea of viewing activities from the perspective of a young child. If you look at a two dimensional picture representing a three dimensional scene, you will notice that irrespective of the real size, anything in the foreground will appear larger than anything in the background – because that’s how we perceive it. I’m thinking of a picture in one of our training rooms which has mountains in the background and trees and birds in the foreground.

The trees tower above the mountains and yet you automatically accept that the mountains are far bigger. So, from a primitive perspective, as a person or object approaches and gets nearer to you, it appears to get bigger, increasing in height. When you APPROACH a person, you ‘go up’ to them. Similarly a runner can ‘romp up’ to the finishing line, or a friend can unexpectedly turn up etc. _________________________________________________________________________

In my experience, all prepositions, adverbs and phrasal verb particles can be illustrated and demonstrated as shown in the examples above. Understanding how a language works is helpful for motivating students to continue exploring and discovering, but you only really learn it by engaging with it. You need to help your students ‘notice’ authentic examples. Depending on their level, find an article or story which interests them and get them to underline all the particles. Ask them to identify the primary meaning of that particle and then discuss its meaning in the context in which it appears.

An exercise which my students like is when I, or even better, they remove the particles and replace them with a symbol to identify. E.g.

They’re pulling the old houses — and putting — new ones in their place.

After the old company closed — they started — a new one.

Eat –! We need to get moving.

They handed — the keys to the new owner.

That’s an interesting proposal. I’d like to think it –.

12 Responses

Peggy Tharpe

Brilliant! Rita Baker has written a truly fascinating account of phrasal verbs, starting with their origins and ending with easy ways to teach them.

05/02/2016

James Heywood

This is one of the best blog posts on Phrasal Verbs that I have read in a long time. I like your approach, probably because it agrees with mine. You don't shy away from the grammar associated with teaching multi-word verbs and you also introduce the necessary visual element needed for students to grasp the meaning of the particle. There will never be a simple way to effectively teach Phrasal Verbs, though if more teachers take on your ideas, they will be more effective teachers. Well done for a thoughtful, well-written blog post.

06/02/2016

Doris Graf

Thank you, Rita, for this approach to teaching phrasal verbs. I'll be using it with my dual study students. Very valuable.

06/02/2016

Judy Thompson

"If you can't explain it simply you don't understand it well enough” Albert Einstein. Once again Rita Baker showcases her deep, clear understanding of the English language by explaining arguably the most complicated aspect of English in her simple, logical, irrefutable way. Thank you for the wonderful article.

06/02/2016

Teresa A. d'Eca

Rita, you make a complex topic so simple and intuitive. Love your approach, as always. Kudos on a great article!

06/02/2016

Gillian CADIER

Marvellous! Thank you for this clearly explained method of working on phrasal verbs.

09/02/2016

Nalini

A wonderful approach to teach a concept that is intuitive. It's well thought out. Thank you!

09/02/2016

Louis Raubenheimer

An interesting (p)article. Thank you!

09/02/2016

Abdulhakim Belaid

Dear Rita, It is indeed a very intersting and it summarizes the whole story of phrasal verbs, especially the " get " and it's particles Well done Hakim

10/02/2016

Christine

This is so interesting. As I teach exam preparation I´m unlikely to use your suggestions very much as the students are in a hurry to pass their exams. But as an item of interest for me, this article is fascinating. Having said all that, I´m sure I will be able to use many aspects of your teaching suggestions. Thanks.

10/02/2016

Gary J. Cohen

Many of what you call "phrasal verbs" are actually just verb phrases or simple collocations that do not amount to phrasal verbs. "Explain over" is one such example. You need to be clear on what a phrasal verb is, and what is its function.

10/02/2016

Rita Baker

Not sure what you mean by 'you need to be clear on what a phrasal verb is, and what is its function'. How do grammatical labels help students to communicate? Do you mean by 'explain over', to re-explain or explain again? It's not an expression I personally use, but it that is what you mean, then it can be very easily explained in the way that I've presented other examples in my article, and I'd be delighted to expand on it.

19/08/2016