Elocution Teaching and Its Place in ELT

Tiptoeing through the minefield of international business communication in itself is already stressful enough, as speaking another language is not merely about learning several words and grammar structures. A skilled communicator indubitably needs to be able to seamlessly master his receptive as much as productive skills, while carefully avoiding cultural pitfalls and minding his elocution. That’s right, elocution, which comprises correct pronunciation and connected natural speech.

The so-far insignificantly acknowledged appendix that is at best practiced for a couple of minutes in our EFL classrooms, if at all, is crucial in communication and yet very few people seem to realise this, or if they do, not much is done about it. Are we seriously in for just standing by as our students keep mixing up “Tuesday” with “Thursday” when setting up an appointment, or do we finally admit that we need to tackle the elocution issue?

It is understandably a thorny matter, as many would argue that WHAT is said is far more significant than HOW it is delivered.

However, we might want to reconsider this latter assumption when we realise that our clients’ performance in product pitches and presentations are not in line with what they are aspiring after, even if they are advanced learners. In a highly competitive environment, nuances make all the difference.

We are human beings, after all, and as such, we make our decisions based on a multitude of factors, not least on our impression that is formed on the speaker’s skills to involve his audience; in other words, his elocution skills. Who would you rather do business with – Giovanna, who is regularly nervous during her presentations, never making eye contact with her audience, stumbling over her words and reading her speech, or Martina, who clearly states the purpose of her speech, reacts to subtle non-verbal signals from the audience and goes out of her way to be clear about what she says?

Communication breakdown

But even native speakers are not entirely off the hook when it comes to being active players in an international business context. It is imperative that there be more awareness about how Anglophone companies (might) miss out on tremendous opportunities due to communication breakdown. Non-native businesspeople keep complaining about the thick regional accents their native counterparts address them with.

Mixed with a fast pace and poor enunciation, it adds up to the perfect recipe for the non-native speakers to be humiliated (they eventually have to resort to asking for an email) and the native speakers to remain frustrated as they realise that they were unable to get their message across. It is thus high time that native speakers finally started to cut their international colleagues some slack and learned to grade their accents and choice of words.

Taking a holistic approach

I would argue that the question of successful business communication goes beyond single aspects of language like grammar, vocabulary, and even pronunciation. We should instead be tending towards a holistic approach.

It has recently dawned on me that language comprehension is primarily subject to a phenomenon I like to call word holism. The latter is a concept based on Ferdinand De Saussure’s paper model in which the significant (that which means) is inseparably connected to the signifié (that which is the object of the meaning) like two sides of the same piece of paper.

There are more things to consider

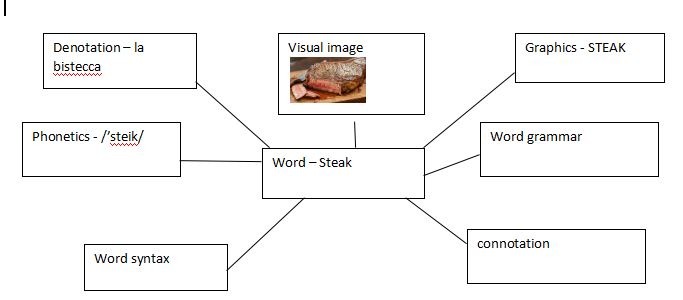

There are some limits to Saussure’s model, though, as we need to consider far more layers. A word has a denotation (a neutral, objective meaning, if you will), it evokes a prototypical visual image in the speaker’s thoughts, it uses socio-cultural graphics, phonetics, word grammar (or clusters, meaning that the possibility of combining words is finite), word syntax (word order) and sometimes a connotation (a subjective association with the word). If the connection of any of these layers is non-existent, hazy, or interrupted, the student will fail to understand the word.

For instance, if the student’s mother tongue interference prevails so much as to let him mispronounce a word, he won’t recognize that word once he hears the correct version. It will be incomprehensible for him. Likewise, communication will be obstructed if the same student pronounces the word differently from the standard convention. The expression “No way!” can be perceived as an exclamation of surprise and disbelief or blanket rejection. It all boils down to; you will have guessed it, elocution.

Possible Interruptions in connections:

- In case you don’t know the English word for the Italian “bistecca,” there are no connections at all.

- The connection to graphics becomes questionable if the word is misspelled (stick/ stack)

- The phonetics connection is interrupted if the word is pronounced wrong (e.g.,/’stik/ or /stæk/

- The link to word syntax becomes loose when the word order isn’t correct: “I like a steak juicy.”

- The connection to word grammar becomes loose when the word is used with a wrong structure: “I like eating many steak.”

- Connotation might vary based on the country – Thinking of a steak would be highly inappropriate in India, for example.

Petrichor

“The limits of my language are the limits of my world.” – What Wittgenstein was driving at with this maxim was that we could only imagine something if we have the words for it. Yet does that imply that if we don’t have a word for a concept, it doesn’t exist? Not hardly.

The fragrance of freshly fallen rain on a balmy summer evening is something most of us have experienced at some point in their lives. Yet, we tend to dismiss the concept as “fuzzy” or “hard to grasp” until we discover the word that perfectly fits this definition: petrichor.

The inseparable connection between a word and the concept behind it is one of those universal dichotomies that maximizes our brain activity or, to use Wittgenstein’s image, allows us to push our limits further, in the eternal quest for limitless knowledge. In our mother tongue, we make those connections over a time of several years and even decades, while we impose on ourselves to achieve the same result in a foreign language in much less time, as we are often driven by the need to communicate.

False projections

When acquiring another language, we automatically lay the language pattern of our mother tongue over the target language. Granted, this is a natural and genuinely effortless process, but unfortunately also the crux of the matter; this is where the mispronunciation of words stems from.

To make things worse, the (false) projection of our linguistic concept onto the target language is additionally fuelled by what we hear other people around us say. Unless we are looking at the case of language enthusiasts who aim at perfection, most learners will settle for the wrong pronunciation and hardwire a false connection that will stick tenaciously for a long time.

Let students take responsibility

As we are crossing over into a new era of language coaching, rather than teaching and leaving behind the outdated mono-dimensional classroom in which a teacher used to dictate what had to be done and wouldn’t allow his students to do more than regurgitating what they were told without thinking much, we are now discovering the potential of letting the students take responsibility for their learning journey not least by tapping into the discourse of making associations. Everything in life is connected, starting from the tiniest particle in our body, over the complicated neural connections in our brain, and up until the galaxies of the universe, so why do we still separate specific skills from others when it comes to language learning?

6 Tips for Using Project-Based Learning in ESL

Regaining confidence

In my function as a presentation coach who is primarily concerned with facilitating her students to perform well during public speeches, I have witnessed bigshot managers who were at their wits’ end, as they were unable to meet the expectations that were placed on them. It was not until we broke down their scripts into palatable pieces that they regained their confidence.

We commonly first work on the correct pronunciation of individual sounds and stresses and then on word clusters before turning to enunciation, i.e., sentence melody and connected speech. The vast majority of corporate EFL students are highly trained in their specific fields but tend to slack off when it comes to speaking English. It is, therefore, the language coach’s job to highlight differences in elocution between the student’s mother tongue and English.

Connected Speech: What Happens During Ordinary, Spontaneous Speech?

Grabbing attention

One significant difference, for example, between English and most other languages, is that the former uses very high pitched tones at the beginning of a sentence to raise attention and will go down at the end of a sentence to signal closure. Failing to adopt this melodiously wavy sound pattern inherent to English, a speech will automatically sound monotonous, and therefore, boring. The last thing you want is to do is lose your audience’s attention.

Natural elocution makes any type of presentation interesting and engaging, where a good accent sells, especially in the UK, where class prestige still depends on it. I’m not saying that a good accent will inevitably lead to success, but at least it will make your interlocutors more receptive to what you have to say. A successful speaker will hook his audience with his engaging voice and convince them with the content.

Making conversation more appealing

No matter what you do in your life, whether you work in sales, you are a doctor, a lawyer, a student, a taxi driver, or only use English for traveling, your accent will help you to sell your product, simplify general conversation, convince the jury or reflect well on the tourist you are giving a ride in your taxi. In a nutshell, your accent will make a conversation much more appealing, while boosting the speaker’s self-confidence. Communication is all about curiosity and a genuine interest in another person. Don’t let pronunciation keep you from this, and let us finally concede the rightful place to elocution in our EFL classrooms.

How to Make Conversation Classes More Meaningful

______________________

Language learning is teamwork and I am grateful and honoured to have been welcomed and trained by the best: Cristina Faita of Melius Solutions SRL, who has given me invaluable opportunities to perfect my teaching style, Rachel Paling of ELC (Efficient Language Coaching) who has opened a door to a whole new universe of possibilities and Sharyn Collins who has inspired me to become a voice coach. Mighty ladies.