Why Evidence Matters

Evidence in education is something that is being discussed more and more often in talks, blogs and articles, so it seems like a good time to throw my thoughts into the mix. I think that it’s important at this time, as it seems to me that EFL hasn’t had a particularly strong relationship with research up to this point, especially regarding how the practitioners (teachers) view the work of the researchers.

Two attitudes to evidence

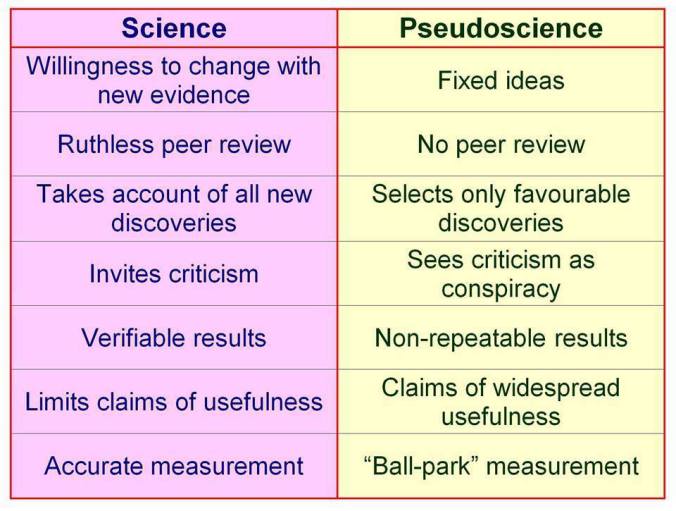

Generally speaking, I think there are two types of people when it comes to evidence. The first are the people who think that the properly carried out studies are a necessary path in order to progress. The second group aren’t worried about such things, they prefer things like ‘gut instinct’, what they see in front of their eyes, and anecdotes. It seems that there is a lot of the latter in ELT. These two different approaches can be broadly compared to people’s view about science, summed up in this chart:

Context is king

But when it comes to education, specifically language education, it can be a bit more difficult as we don’t have that basic set of rules that tell us exactly how to teach a language. Context is such a pivotal part of this discussion; the age, social status, physical and emotional health, academic background, family background, and personal motivation of both the teacher and the learners, as well as the physical environment where the learning takes place, the time of day when the lessons occur and the expectations of the institution where they happen will all have an affect on the final outcome – the ability of your students in English. These factors combine to make my classes not just different from yours but different from each other and subsequently it seems almost pointless to think that we can create a complete, unifying theory of language learning.

Everything is not as you think it is

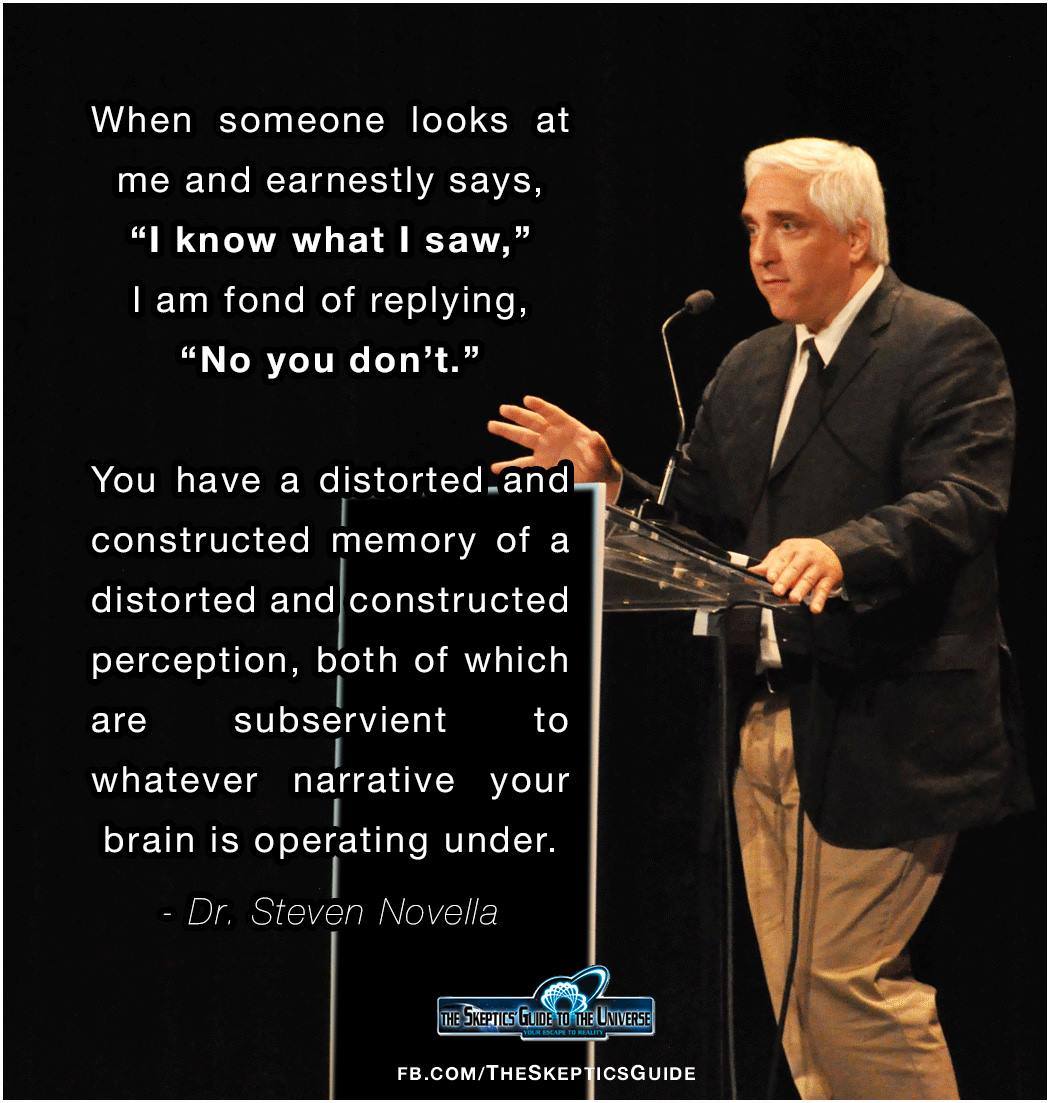

In the long run, that may be the case but I would argue that rational, evidence based approach is still vital if we want to move forward towards a better understanding of what we do in the classroom. I think the mistake that the second group of people, the ‘gut instinct’ types make is that they overestimate humanity’s ability to understand what we see in front of us. There are countless examples in psychology of ways that we are deceived by our brains into perceiving things as we wish to see them, not as they really are. Human beings are very unreliable witnesses, especially when we have a stake in the outcome. This is evident in how people react to the idea that their belief has been proved to be wrong, or is at least unproven.

A few months ago, I read this comment, which was made in response to a criticism of multiple intelligences and neurolinguistic programming:

Although I have yet to come across any scientific proof of either Gardner’s multiple intelligences or NLP’s VAK styles, anyone who has ever taught a group of teens cannot deny their existence.

This is the kind of thinking that gets in the way of progress in our field. The first issue is that the speaker expects to “come across” evidence and this is unlikely, as it rarely lands in our lap. If they have a genuine interest in checking the data, they will have to go out and find it (which I concede is not always easy). The second issue is that the speaker accepts with absolute certainty the relationship between what she does in the classroom and with her perceived end result. She is certain that one leads to the other, but as I said above, the classroom is a complicated place and the student is a complicated individual. If only the relationship between what we do and the students learning was as simple and direct as she suggests.

Why evidence matters

As progressive individuals, interested in the development of our field, we need to accept, with humility, that we are all flawed witnesses and poor judges of things that we are invested in. It’s a weakness we all share, including the more Spock-like among us. Accepting our human flaws and knowing that well-conducted, extensive research is required as a part of the process of understanding what we do is only a threat to what you believe in if you have chosen to make it a fundamental part of your teaching identity. I’ll be the first to admit that I have beliefs about my teaching that are completely evidence free, but what it is even more important to me is that if you can disprove what I think with well conducted research, I will happily change my mind in a heartbeat. It’s what rational thinkers and good scientists do, and I aspire to be like them.

What will it take for me to change my mind?

An effective question to ask yourself is “what will it take for me to change my mind?” If the answer is “nothing”, then you need to be aware that this is a path that can only lead to the shutting down of any constructive dialogue and an inability to progress, possibly to the detriment of your students. And I’m certain you don’t want that.

Progress is impossible without change, and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything. – George Bernard Shaw

I’d love to know what you think, so please enter your comments in the box below.

18 Responses

Ron

Excellent article, and I agree wholeheartedly. I recall reading that very comment about MI and NLP and shaking my head in incredulity.

12/01/2017

James Taylor

Thanks Ron, that was my reaction!

18/01/2017

Philip Longwell

I generally agree with you James about an evidence-based approach. Isn't the raison d'etre of the Research SIG, nonetheless, to forge a stronger relationship between EFL and research? I would be interested to know what Richard Smith thinks.

21/01/2017

James Thomas

Hi. I've been giving this idea some considerable thought over the last few months. It has been firstly necessary to separate data, info and knowledge from beliefs, as I see the last of these as a filter and tending towards the right hand side of your table. And I have a problem with small-scale and local research being generalised. Perhaps our field would benefit from meta-analyses that would identify trends among them. We sometimes get these in the introductions to anthologies of research papers.

21/01/2017

Geoff Jordan

You point out how difficult it is to carry out scientific studies of language learning,but you don't explain how these difficulties can be overcome. You assert that a rational, evidence based approach is “vital”, but you make no attempt to suggest how such an approach should proceed. So your article does no more than make the trivial claim that it’s better to examine the evidence and keep an open mind than to trust your gut instincts and say that nothing will make you change your mind.

21/01/2017

Mike Harrison

I'm finding myself in agreement with Geoff Jordan a bit here. This post seems incomplete: you're stating a valid point that evidence should be something that we need to work with in language teaching, but what's missing are the tools and tips to do this. There could have been links to posts like the one I was re-reading the other day, Dale Coulter on some frameworks for building up a series of reflections on teaching practice that could lead to an action research project: https://languagemoments.wordpress.com/2011/11/13/practical-ideas-for-retrospective-planning-in-a-reflective-journal/ Maybe you're planning to write a follow-up? Also sources and links would be appreciated for things like the table you've included in your post (unless it's your own work?)

22/01/2017

Penelope Roux

Good points in the comments above. I have commented on British Council posts in the past pointing out that all too often they share blogs and articles that have a tendency to 'trash' the work of EFL teachers rather than offer constructive advice and encouragement. What many TEFL teachers lack, unfortunately, is a solid foundation in pedagogy. This may be less of an issue with non-native TEFL teachers: many countries require or expect higher degrees including credits in pedagogy for all teaching posts. But certifications such as CELTA focus essentially on the language (philology, phonology etc) and don't require an in-depth knowledge of pedagogy nor do they encourage on-going research-based professional development. Too many EFL teachers just don't have the competencies needed to make evidence-based assessments of the resources and methods they are using. I don't think it is always an 'attitude' issue. Organisations such as the British Council, Cambridge English, etc could do so much more to regulate the industry (after all, the global business of teaching English - especially to adults - is an industry) and promote excellence in the profession.

22/01/2017

James Taylor

I must confess, Phil, and say I haven't looked into the Research SIG too closely, but I would be delighted if that was the case.

23/01/2017

James Taylor

I would certainly welcome these suggestions, James. Although it wasn't really the focus of this article, it is clear that there is a lot of work to be done in this regard.

23/01/2017

James Taylor

You're right Geoff in that I don't tackle those aspects of the issue, and while I agree that they are absolutely worthy of further discussion, that wasn't what I was trying to achieve with this article. You assert that my point is trivial, and I can see from academics point of view why it would seem that way, but from speaking to practicing teachers throughout the years, I have seen considerable resistance to even the notion that they should change their teaching practice based on research. Find a learning styles fan and try and change their mind if you want to test that. It may be trivial to you, but it isn't to them. So I agree that the article you wanted should be written, and I'd like to read it, but it wasn't what I was trying to achieve here.

23/01/2017

James Taylor

Thanks Mike. I've covered most of this in my comment to Geoff above, but I'd just like to add that this post is not meant to be a comprehensive guide to evidence based teaching, it's more a nudge to those who are resistant to the idea. But I could have added a "if you'd like to know more" section, it's true. And I can't find an original source for the table. It's been shared around a lot but I can't find who created it.

23/01/2017

James Taylor

Thanks Penelope. I sincerely hope that you don't think this article is trashing the work of teachers, as I particularly tried to make sure that this article didn't come across that way. You make some excellent points regarding training and pedagogy which I wholeheartedly agree with, although it's worth remembering that this type of teacher is most definitely in the minority in comparison with the number of teachers who work in the state system. I think it's also worth pointing out that a higher level of training doesn't insulate you from pseudoscientific thinking. Many people who hold what I would consider to be irrational, non-science based opinions outside of education (conspiracy theories, anti-vaccines etc) are well-educated. On my DELTA course I was encouraged to mention learning styles, something I found to be very disappointing. So while training is crucial and probably the real key to future progress, it does require an attitude shift in those who are resistant to evidence based teaching practice.

23/01/2017

Adam BeLe

This might be of interest in light of previous comments. A new course being piloted by International House. Maybe a tentative step in the right direction. http://ihworld.com/online-training/course/ih_action_research_course

24/01/2017

Phil Wade

I'll add my 10 pence worth. I did a UK government postgrad in teaching and in no way did it equip me to teach as there was nothing on methodology. We learned the curriculum and did some tasks and looked at materials. Lectures were on Cognitivism vs Behaviourism etc and we looked at the usual multiple intelligences, ZPD etc. I had done a CELTA before and it was only thanks to that course that I passed my degree. I later did the DELTA, an MA TESOL and am completing a PhD in Educations and I'd say that the CELTA is the only one that can teach you to teach. Thus I'd also say that the CELTA/TEFL community really know what works and can manage and handle classes. The pedagogy I got from studying methodology and linguistics from the MA was too theoretical and was very hard to apply to my work. I would also go so far as to say that the TEFL method has influenced mainstream ELT education to such as point that I have seen many people using it in universities while the content teachers often rely on a lecture method. This is an old old old discussion and I'm not a fan of claiming natives are unqualified while non-natives are as it is wrong. Teachers are teachers. The CELTA is very effective for teaching in a language school. An MA is very good for teaching content lectures and seminars. The CELTA was made, as far as I know, to give a quick introduction and the essentials to people going to travel or just to teach in a school for a summer or a year or two. It is not recognised in some countries and it is not MA level. You can't compare it to an MA or a BA in Education. As far as I know, we have the CELTA then the DELTA which is in the UK classified as MA level and then their is the Cert iBET and various exam training courses. There are regular British Council inspections too. I worked in a big chain and it was very controlled and professional. It was far less in some other organisations I taught in with alleged 'experts'. I will also add that during my postgrad teaching placements I saw a lot of MA level teachers with 5-40 years experience cover lessons in schools and almost every single one failed. Some walked out after 10 minutes. Others just gave worksheets and sat and read. This is a big failure of the government's system. They don't prepare people to teach and handle normal students. even now after almost 20 years in education, I still hear teachers say "I talk and if they listen, they listen. If they don't want to and prefer to play with their phones then fine". I might be wrong but this would never happen in a CELTA style class as we are all about control and learning. Of course, I HIGHLY recommend any serious teacher does the DELTA and an MA and I think many people reading this have gone down that path.

24/01/2017

James Taylor

Thanks Adam, that looks interesting. I wonder how popular it will be?

24/01/2017

James Taylor

Thanks for this Phil, it adds valuable context to this discussion. It's an interesting perspective, particularly on the CELTA which I hadn't considered before. What I would welcome on course like this is some component that encourages new teachers to have an awareness that research is going on and that they should be responsive to it.

24/01/2017

Phil Wade

My pleasure James. I see the CELTA as a skill builder and academic courses as giving you knowledge. These are VERY different. The CELTA does what it says on the box i.e. you leave being able to teach and handle TEFL classes with adults using coursebooks. You can get a job the next day and teach. Do an MA then go to work in a TEFL school and it will be hard. Yes, you might know about SLA and the 'classic' methods but won't have been trained and have developed real teaching skills. I think the TEFL industry and the academic uni and primary and highschool teaching worlds can help each other. We shouldn't be competing or comparing and especially branding people as whatever. If a school hires a CELTA teacher they know what they will get and for most it is what they want. A CELTA grad fits perfectly into a British Council accredited school that uses EFL coursebooks from CUP, OUP etc and prepares students for Cambridge exams. Ask the CELTA grad to teach beyond their comfort zone and there can be issues. Horses for courses.

25/01/2017

Philip Longwell

I've tweeted Richard Smith's short reply..

25/01/2017