Critical Thinking And English Language Teaching

Critical thinking is not only definable but teachable. That’s good news in general, but does this mean critical thinking has a role in ELT? Atkinson questions this notion. He argues that critical thinking should not be taught to language learners because:

- It is neither definable nor teachable.

- It is exclusive and reductive.

- It is culturally-based.

- Critical thinking skills are not transferable.

We have already examined claim one in some detail. Claim number two is highly debatable and holds little practical weight. It is the last two claims that deserve focus here.

First, is critical thinking a western construct? Most research shows that critical thinking – the seeking of reasons and alternative explanations –is quite common cross-culturally. However, the degree to which critical thinking is employed is controlled by culture and socialization. In some cultures, asking for reasons or challenging premises is considered taboo – silence, imitation, and conformity are instead features of the model student. In some cultures, education in schools is through memorization not reasoning.

Is it wrong to impose the critical thinking on students from cultures where it is not as cherished? That really depends. If the goal is to undermine the cultures from which students come, then imposing critical thinking is not a good idea. However, even traditionally “non-critical” cultures (in the Western sense) like China and Japan have expressed the desire to foster stronger critical thinking skills. The idea of undermining culture seems far-fetched, in particular because critical thinking does not replace other modes of thinking but rather works in conjunction with them. This is why you can be both a critical and creative thinker. They are not mutually exclusive modes of thought.

In addition, we must consider students’ needs. Will students have to interact with people from cultures where critical thinking is more overtly used? Are students trying to study in universities in which critical thinking is an important facet? If so, then, yes, we must teach critical thinking.

Davidson, in responding to Atkinson’s arguments, claims that “we as L2 teachers have good reason to introduce higher level students to aspects of critical thinking. If we do not, our students may well flounder when they are confronted with necessity of thinking critically, especially in an academic setting”.

Our final question regarding whether critical thinking should be taught to language learners is if it is transferable outside of the context of the language classroom. Research has shown that critical thinking can be transferred across domains, but, like the learning of critical thinking itself, is not an easy process (see Halpern [1998] for an overview). Some researchers recommend a “writing across the disciplines” approach to help expose students to the different permutations of critical thinking. Transferability is possible if it is part of critical thinking pedagogy.

All of this begs two more questions: 1) is teaching critical thinking to English language learners possible and 2) how does one actually go about doing this? The answers to these questions are related.

A quick search of research on ESL/EAP and critical thinking reveals a number of studies that have shown success in the teaching of critical thinking. Most of this comes through reading and writing instruction. Here are some ideas from the research.

General Strategies and Recommendations

A lot of the research points to explicitly teaching critical thinking strategies. Dalton recommends these strategies:

- Connecting

- Evaluating

- Applying

- Selecting

- Prioritizing

- Specifying (use/purpose)

- Contextualizing (use/purpose)

- Describing

- Exemplifying

- Linking

- Developing

- Concluding

For students from more oral cultures (e.g. the Middle East), Nezami recommends using group discussions before reading to help foster critical skills. Nezami also recommends the explicit teaching of strategies, including summarization.

Parrish and Johnson recommend this same explicit strategy instruction but also emphasize graphic organizers as a way to help analyze a text.

Wong has created a curricular resource guide which offers a systematic ways of organizing and teaching critical thinking skills in the area of reading. The guide is available in her dissertation (pages 77-146). It is organized as follows (p. 72):

- Interpreting texts based on personal knowledge

- Synthesizing from multiple sources

- Organizing and analyzing ideas

- Identifying assumptions and evaluating information

Peer editing

Mulnix highly recommends using the writing process to help foster practice critical thinking. Specifically, she recommends self- and peer-editing “with an eye to weeding out fallacies and also towards improving their argument pattern”. This is something that can easily be applied to writing in ELT.

Argument mapping

Both Mulnix and van Gelder have argued for the extensive use of argument mapping, which is essentially a form of graphic organizers that help in analyzing an argument. Mulnix argues that by argument mapping, the organizational structure of a writing piece is often revealed and the writing of the paper becomes “straightforward”.

Close Reading

Close reading is a deep reading of a text that involves annotations, patterns, contradictions and similarities, and question asking. It is a great approach to reading. Harvard has a brief introduction to it here and a really good guide with practical examples and exercises can be found here.

Transactional Reading

Transactional reading is a form of close reading in which texts are interpreted through differing contexts found in the text, often placing the readers themselves in the text to interpret it. Gomez and Leal used transactional reading of urban legends to promote critical thinking skills among their students. The authors had students read short urban legends individually, completing comprehension worksheets and then critical post-reading tasks that were based on transactional reading. Following the individual reading, students worked in small groups to discuss the reading, followed by whole class discussions. These discussions were meant to help students “to evoke multiple meanings from the texts and to reflect critically on this process”.

More Practical Examples

Lower-Level Classes

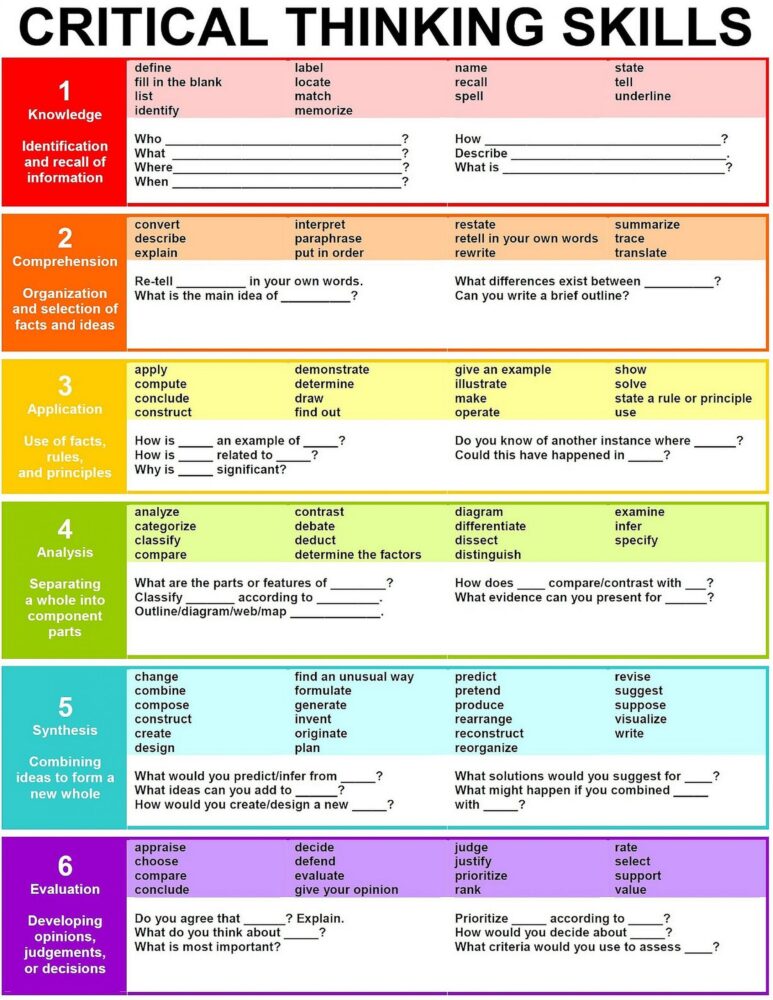

In my lower level classes, I do utilize Bloom’s taxonomy as it serves as a structured introduction to critical thinking. In particular, I use this chart with special attention on the question prompts (I have never used verb clusters):

Typically, after completing various comprehension questions for readings and listenings, I begin utilizing this chart. At first, I typically draft a question for each level. After students are used to the question types and the thinking required of them – usually after several texts and question rounds, students begin drafting their own. Answers are given through short-answer writing and often through small group discussion. This has been a very successful activity in terms of getting students to move beyond basic comprehension questions.

Furthermore, that higher level skills are not necessarily more difficult than lower level skills is supported by my experience with this chart. Students have as much difficulty answering level 5 and 6 questions as they do level 2. The research on critical thinking that shows engagement in critical thinking is more important than addressing a hierarchy becomes very clear after working with this chart. Still, it serves as a very good introductory tool and I highly recommend it to any teacher.

Other activities for promoting critical thinking include

- A Claim Chart in which students read a paragraph or article and find claims, evidence, and explanation of evidence. This is very similar to the argument mapping I referred to last week.

- Fix the Claim, in which students read sample paragraphs, identify a problem with claims (usually lacking evidence), and then re-write the paragraph to include a properly worded claim, relevant research that supports the claim, and full reference and citation.

- Critical Thinking Role Play in which students are given a situation and a role (e.g. different stakeholders in a pharmaceutical company that disposes of chemicals in the sea), research their role and find evidence for their claims, and then finally hold a small-group discussion based on their roles.

There are a lot of ideas out there, but they all seem to share an overlap: critical thinking needs to be deliberate, explicit, and extensive. Students need to engage in critical thinking in order to learn it. How they engage in it can be realized in a multitude of ways but, in general, these engagements typically address several aspects of the polysemous definitions of critical thinking.

Critical thinking exists cross-culturally, has consistent and identifiable aspects, and is teachable in both L1 and L2 contexts. Critical thinking is a buzzword that rightly deserves attention, as it is an important and valuable skill to possess. It is my hope that by recognizing these aspects of critical thinking it moves from the empty jargonized position it occupies and moves toward the forefront of pedagogy and instruction in English language teaching.

[jbox title=”References”]

Atkinson, D. (1997). A critical approach to critical thinking in TESOL. TESOL quarterly, 31(1), 71-94.

Case, R. (2013). The Unfortuate Consequences of Bloom’s Taxonomy.Social Education, 77(4), 196-200.

Dalton, D. F. (2011, December). An investigation of an approach to teaching critical

reading to native Arabic-speaking students. Arab World English Journal, 2(4),

58-87.

Davidson, B. W. (1998). Comments on Dwight Atkinson’s” A Critical Approach to Critical Thinking in TESOL”: A case for critical thinking in the English language classroom. TESOL quarterly, 32(1), 119-123.

Hernandez, M. L., & Rodríguez, L. F. G. (2015). Transactional Reading in EFL Learning: A Path to Promote Critical Thinking through Urban Legends.Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 229-245.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Disposition, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring.American Psychologist, 53(4).

Moore, T. (2013). Critical thinking: seven definitions in search of a concept.Studies in Higher Education, 38(4), 506-522.

Mulnix, J. W. (2012). Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 44(5), 464-479.

Nezami, S. R. A. (2012). A critical study of comprehension strategies and general

problems in reading faced by Arab EFL learners with special reference to Najran

University in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Social Sciences and

Education, 2(3), 306-317.

Parrish, B., & Johnson, K. (2010, April). Promoting learner transitions to post-secondary

education and work: Developing academic readiness from the beginning. CAELA

Network Briefs. Retrieved June 1, 2015 from

http://www.cal.org/caelanetwork/resources/transitions.html

Ramanathan, V., & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Some problematic” channels” in the teaching of critical thinking in current LI composition textbooks: Implications for L2 student-writers. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 7(2).

van Gelder, T. (2005). Teaching critical thinking: Some lessons from cognitive science. College teaching, 53(1), 41-48.

Wong, B. L. (2016). Using Critical-Thinking Strategies To Develop Academic Reading Skills Among Saudi Iep Students.

[/jbox]