How learning a language can benefit your teaching

My major embarrassment as an EFL teacher is not being fluent in another language. However, all that is about to change. I want to show you how learning a language can benefit your teaching.

Two months ago I moved to Bangkok to take up a post with the British Council. This is the sixth country I’ve taught in, and this time I’m determined to learn the language. No excuses. If I don’t have time, I’ll make time. If the language has little application outside the country, who cares? If 99% of Thai’s can’t understand a word I’m saying at the moment, it’s ok. Tomorrow that might only be 98%, next week it might be down to 97%. I’ll get there, I just need to listen to my own advice as a teacher – be patient.

It’s fun learning Thai, but what’s surprised me is how much I’ve reflected on my own teaching since becoming a learner again. The experience had led me to revisit EFL literature, rethink some approaches and reinforce the benefits of certain learning strategies. I already feel like my teaching is improving as a result of my learning experiences. Here are a few ways that learning a language has influenced my practice over the last couple of months.

A Focus On Useful Language

It’s amazing how quickly you can absorb information when you first start learning a language. When I met up with an old colleague after being in Thailand just 2 weeks, he said it was nice to see me ‘at the leaps and bounds stage’. He was right – since the first few weeks I’ve slowed down a bit.

I benefitted a lot from my teachers approach in the first month as it was different to what I expected. Some of the usual beginner vocabulary featured – learning the colours, the days of the week, clothes, foods, etc. However, the focus was far more on functional language. I learnt structures for giving advice/making suggestions, bartering at the market, making polite requests, and giving directions all in my first two weeks. Learning so many useful phrases to apply in my natural surroundings has given me a lot of confidence. It’s also meant I have more money to spend on my language classes as I know how to get a discount on my fruit and vegetables!

I’m currently teaching a lot of Elementary level classes, with most of my materials for adult students already produced in-house. In light of my own experiences, I tend to look over the pre-planned lessons and seek opportunities to teach more functional phrases when relevant. In terms of teaching EFL, I feel this notional approach may give learners greater chance of having an authentic interaction when they meet English speakers in their own country.

The result of this change to my teaching is twofold. Firstly, students become very engaged in stages of my lesson involving teaching a function – often through dialogues. The copious notetaking and willingness to perform roleplays (and respond to feedback on pronunciation) suggests to me that learners can really see the purpose and benefit of what they are studying. Secondly, it’s clear that whilst our in-house materials are very good, they could exploit language functions a little more.

The Benefits of Functional Language

The benefit of functional language input for me as a learner may go beyond the fact that it has a clear purpose. It may be something to do with how I’m storing the language.

The moments I like best in class are when I ask my teacher for a phrase that I really need and she just says it, naturally and with no reference to any structures. In my second lesson, I asked her how to say ‘can you turn the air con up a bit?’ At the time I had a vocabulary of about 10 words, so this was just a chunk of formulaic speech to me. Still, I used it at work a few times that week, then in a taxi twice, and it just stuck. A week later we came to analysing the structure for ‘Can you…?’ in class. I realised that I’d already utilised this structure in real world situations about 10 times, without truly knowing what I was saying. As mentioned, formulaic speech can do wonders for lowering the affective filter. It was great on Day Two of a learning experience to actually perform a function without any difficulty.

The role of the right hemisphere in storing and processing formulaic speech is an idea associated with the neurofunctional theory of SLA, originally proposed by Lamendella. It’s argued that the subsequent analysis of such formulaic utterances by the left hemisphere is required in order to utilise the language form in freer speech.

This learning experience has really influenced how I teach elementary level classes. Revising the neurofunctional theory reminded me of the benefits of pattern practice, although I find it is actually a critique of the method in some ways. During the early stages of SLA I can see benefits in this approach, before the need to get bogged down in structure.

Organized Board and Organized Lesson

There are plenty more practical ways that my teaching had benefitted from being on the other side of the classroom. Whiteboard work is a prime example.

There are plenty more practical ways that my teaching had benefitted from being on the other side of the classroom. Whiteboard work is a prime example.

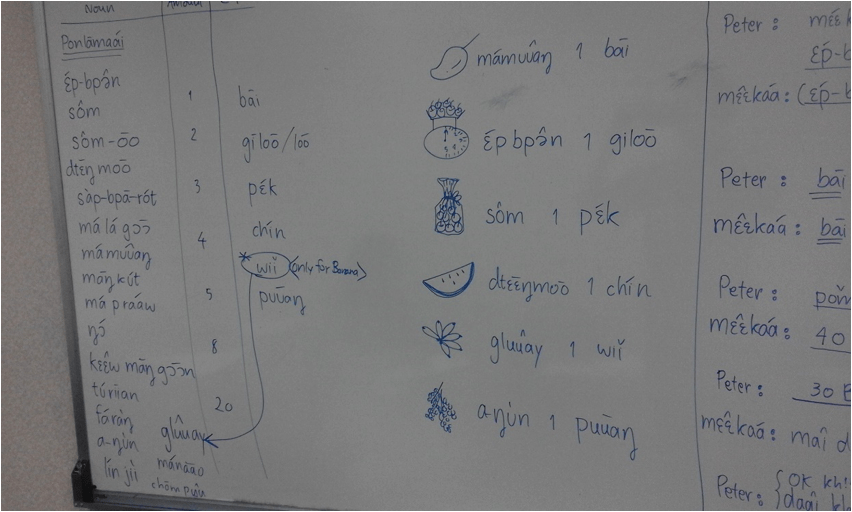

My Thai teacher is so organised. I don’t know how her board looks so neat and tidy. She made me realise just how much I’d come to neglect my own board work – I’ve spent the last month or so addressing this issue. After reviewing some old CELTA literature, doing a bit of detective work in other classrooms, and jotting down some ideas from my Thai classes, I came up with this post on my blog. Above all, the thing I’ve learnt from my teacher is how board organisation may reflect the learning experience. This is why I’m determined to stop my writing tobogganing down the board into oblivion, as it so often does!

Learner strategies

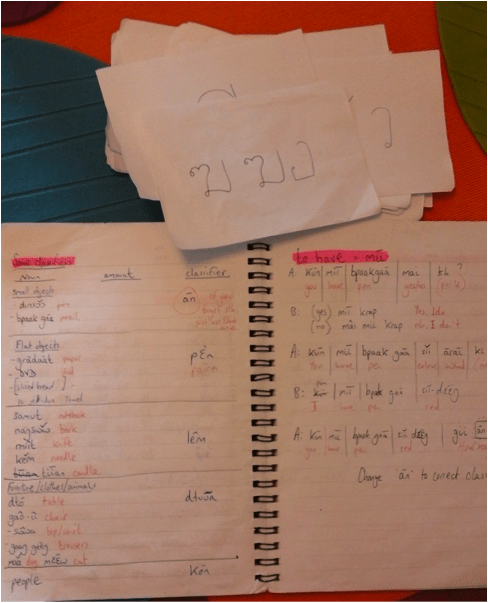

I’m always conscious of what strategies I use as a learner. I also like to observe my own students to try and pick up some tips from them. Most are copious notetakers like me, but I never see any sets of flashcards on their desks. I’ve always found flashcards so useful for revising vocabulary, and at the moment they are helping me get to grips with the Thai alphabet. Of course, I am a bit of a dinosaur – I’m sure they’ve all got revision apps with flashcards on them. I hope so anyway.

I’m always conscious of what strategies I use as a learner. I also like to observe my own students to try and pick up some tips from them. Most are copious notetakers like me, but I never see any sets of flashcards on their desks. I’ve always found flashcards so useful for revising vocabulary, and at the moment they are helping me get to grips with the Thai alphabet. Of course, I am a bit of a dinosaur – I’m sure they’ve all got revision apps with flashcards on them. I hope so anyway.

What works for one person may not work for another, so I normally point students towards possible strategies that could help their learning rather than tell them what’s best. Through my recent learning experiences, however, I’ve become aware that perhaps learning strategies on the whole are being underused autonomously by my students.

For example, translation features heavily in my Thai language classes as I just can’t fathom what’s happening half of the time. Translation has become a more prominent feature in the classes I teach too, which is strange as it means inferencing as a cognitive strategy is all but non-existent. I have let more translation seep into class. I see learners flicking around on their dictionary apps then making some L1 annotations in their notebook, and I’ve become worryingly ok with this. Are they being resourceful or lazy? Should they know better? Do they actually know other ways to deal with unknown words? Either way, I realise that this is something I need to address in both my teaching practice and my own learning.

For an overview of types of learner strategy, a good resource is Macaro.

Every week I’m realising more about the difficulties my learners are facing, just by putting myself in their shoes. It’s leading me to rethink a lot of my approaches and to consider whether certain aspects of my practice are truly beneficial. I am sure many teachers have the same feelings. How do you think that being a language learner has influenced your own practice? Has it changed your attitudes towards certain debates in the profession, such as the use of L1 in class? Has it led to you revisiting theories that may underpin your practice?

That’s enough reflection for now – time to pick up the flashcards!

[jbox title=”References”]

Lamendella, J. T. (1977). General Principles of Neurofunctional Organization and Their Manifestation in Primary and Nonprimary Language Acquisition1.Language learning, 27(1), 155-196.

Lamendella, J. T. (1979). The neurofunctional basis of pattern practice. TESOL quarterly, 5-19.

Macaro, E. (2001). Learning strategies in foreign and second language classrooms: The role of learner strategies. A&C Black.

[/jbox]