Critical Thinking And English Language Teaching Pt. 1

Critical thinking has been a buzzword for some time now. In fact, judging by the research, it has been a buzzword for over a decade. The problem with buzz words is that, over time, they lose a lot of their original meaning and begin to stand for almost anything new or progressive. In addition, it has become an empty rallying cry (“We must teach critical thinking in English language teaching!”) devoid of the very thinking it purports to support.

Why does hearing the cry above make people cringe? Why does reference to Bloom’s taxonomy often cause negative reactions? One reason is because these terms are overused. But is there something more? Are people (rightly) skeptical of these concepts?

There is no doubt that “critical thinking” is buzzworthy. And, if it’s buzzworthy, it must have some importance. So, what exactly is critical thinking and why is it important? I believe the answer to these questions can be framed through the arguments of those who are critical of critical thinking. This article will briefly consider the research on critical thinking and argue that critical thinking should play a central and explicit role in English language teaching.

Can Critical Thinking Be Defined?

There are those who feel that critical thinking can only be defined in broad, subjective terms that are too various to unify. How do you teach something if you can’t even define it? The literature on critical thinking – coming from psychology, education, and philosophy, agrees somewhat with this point. It seems that critical thinking is not readily reducible. It is, rather, multidimensional, or, polysemous. Nevertheless, while the idea of critical thinking may be expressed in various ways, Moore found that these are typically well-articulated and clearly conveyed to students. Moore claims that the variety of meanings may be discipline-based, meaning that psychology prefers certain aspects of critical thinking more so than history, which prefers others. Still, Moore was able to identify some common features which can define the concept more clearly.

According to Moore’s research, critical thinking is:

- A judgement of whether something is good, bad, valid, or true

- rational, or, reason-based

- skeptical thinking

- productive thinking – not only challenging ideas but producing them – coming to conclusions about issues

- carefully reading beyond a text’s literal meaning

- awareness of the entire process

- ethical or activist – in other words, not neutral

Although Moore is not the sole and final authority on what is means to be a critical thinker, it’s clear that critical thinking can be somewhat defined as a concept, though we must accept that its meaning – like many other concepts – “is its use in the language” (Wittgenstein, cited in Moore, p. 508).

Can Critical Thinking Be Taught?

If critical thinking can be defined (as Moore and others have done), then can it be taught? Certainly, it’s important to think critically. No one is arguing it is not. However, many claim that it must be organically developed, or it is a skill that can be encouraged but not learned. The literature, however, shows the opposite. Not only can critical thinking be taught, it can be practiced and refined!

First, we have to understand that critical thinking is hard. Experimental research by Kuhn (1991) shows that a majority of people cannot demonstrate critical reasoning skills. That is, they cannot often justify their beliefs and opinions with evidence.

Van Gelder and Mulnix, mulling over the question of how to teach critical thinking, found some practical advice, much of which is based in cognitive science.

- Examples of critical thinking are not enough – students need to engage in critical thinking.

- There needs to be deliberate practice to master the skill. This includes full concentration, exercises aimed at improving the skills, engaging in increasingly difficult exercises as easier ones are mastered, and guidance and feedback.

- The practice must be repetitive throughout a course.

- Students must practice transferring critical thinking skills to other contexts.

- Students must eventually become aware of the actual idea of critical thinking, including its terminology.

Empirical research on critical thinking shows that it not only can be taught but must be taught. As teachers, we should develop exercises, strategies, and assessments that seek to improve this skill. Mulnix concludes rather poignantly, “To do any less is not only to let our students down, but it is to fail at that very skill we are trying to teach”.

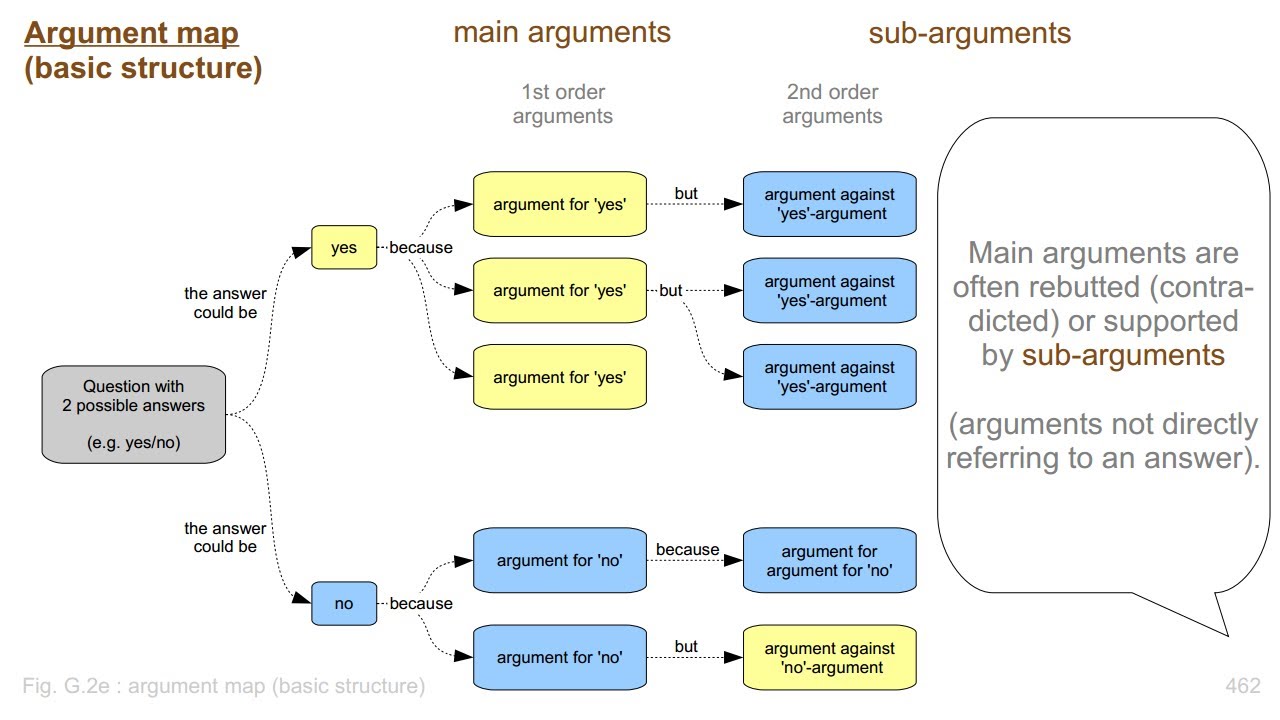

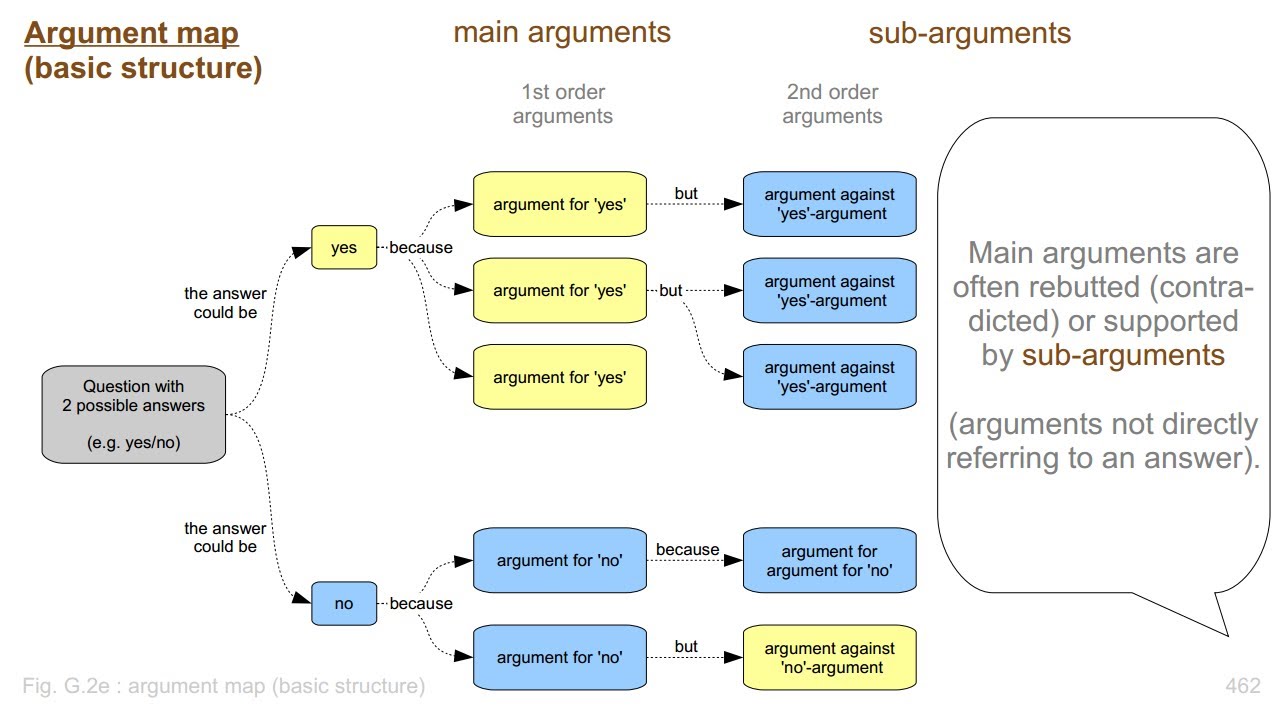

One exercise that has been shown to be effective is argument mapping, in which arguments (including claims, warrants, evidence, etc.) are visually displayed in a diagram. This makes it easy to understand, analyze, and evaluate arguments. Argument maps start with a central premise (i.e. thesis) at the top and include below it evidence or reasons, co-premises (co-reasons), counterarguments and rebuttals, with lines and arrows to show the connections between the ideas.

As a classroom activity, argument maps can first be given as templates that students fill in. Once familiar with argument mapping, they can then begin to construct their own based on analyzing textual sources (readings or lectures) or for forming their own logical conclusions (for discussions, debates, and presentations). By analyzing the arguments written, students can then begin evaluating reasons, evidence, and counterarguments. They can begin questioning the validity of these arguments and suggest their own conclusions or justification. In this way, they are deliberately engaging in critical thinking practice, which, as shown above, is key for developing good critical thinking skills.

Argument map examples:

Wait! What About Bloom’s Taxonomy?

Bloom’s taxonomy is perhaps the most well-known example of critical thinking. It is an orderly, visually-pleasing representation of, as we have seen, quite a large concept – and this is perhaps one reason why it has held educational weight since the late 50s. However, it has come under much scrutiny both for the way it has been organized and the way it has been employed. There is poor empirical basis for the organization of the hierarchy and its implications for task sequencing. “Lower order skills” are not necessarily easier than “higher order skills” and vice-versa. In addition, these “lower” skills are often used in conjunction or even after using the “higher order skills”.

Nevertheless, Bloom’s (revised) taxonomy is still quite common in the scientific literature. A search for “bloom’s taxonomy” on Google Scholar reveals a great deal of peer-reviewed research which utilized Bloom’s taxonomy. So, why the persistence? While the hierarchy may have its weaknesses and its organization may not always represent reality, the levels of the taxonomy do include most conceptions of what critical thinking is, and there is evidence from neuroscience that supports the taxonomy itself. In the video, “What can Neuroscience Research Teach Us about Teaching?”, neuroscientist Daniel Kaufer points to Bloom’s taxonomy as an example of active learning in which, as one moves up the hierarchy, more and more areas of the brain become dynamically activated. In other words, when more areas of the brain “fire together” they typically “wire together”. So, working on higher order skills may not be more difficult than lower order skills, but it may lead to stronger reinforcement of learning.

One of the alternatives to the taxonomy Case proposes is very much aligned with what we have read above about the pedagogical ideas behind teaching critical thinking:

“Understand that inviting students to offer reasoned judgments is a more fruitful way of framing learning tasks than is the use of verbs clustered around levels of thinking that are removed from evaluative judgments”.

[jbox title=”Reference List”]

Atkinson, D. (1997). A critical approach to critical thinking in TESOL. TESOL quarterly, 31(1), 71-94.

Case, R. (2013). The Unfortuate Consequences of Bloom’s Taxonomy.Social Education, 77(4), 196-200.

Dalton, D. F. (2011, December). An investigation of an approach to teaching critical reading to native Arabic-speaking students. Arab World English Journal, 2(4),58-87.

Davidson, B. W. (1998). Comments on Dwight Atkinson’s” A Critical Approach to Critical Thinking in TESOL”: A case for critical thinking in the English language classroom. TESOL quarterly, 32(1), 119-123.

Hernandez, M. L., & Rodríguez, L. F. G. (2015). Transactional Reading in EFL Learning: A Path to Promote Critical Thinking through Urban Legends.Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 229-245.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Disposition, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring.American Psychologist, 53(4).

Moore, T. (2013). Critical thinking: seven definitions in search of a concept.Studies in Higher Education, 38(4), 506-522.

Mulnix, J. W. (2012). Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 44(5), 464-479.

Nezami, S. R. A. (2012). A critical study of comprehension strategies and general problems in reading faced by Arab EFL learners with special reference to Najran University in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Social Sciences and Education, 2(3), 306-317.

Parrish, B., & Johnson, K. (2010, April). Promoting learner transitions to post-secondary education and work: Developing academic readiness from the beginning. CAELA

Network Briefs. Retrieved June 1, 2015 from http://www.cal.org/caelanetwork/resources/transitions.html

Ramanathan, V., & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Some problematic” channels” in the teaching of critical thinking in current LI composition textbooks: Implications for L2 student-writers. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 7(2).

van Gelder, T. (2005). Teaching critical thinking: Some lessons from cognitive science. College teaching, 53(1), 41-48.

Wong, B. L. (2016). Using Critical-Thinking Strategies To Develop Academic Reading Skills Among Saudi Iep Students.

[/jbox]

6 Responses

Sam

Thanks for this really well researched and written article, Anthony. I particularly liked your suggestion of 'argument mapping'. I think it could be a great way for students to plan their academic assignments. I'd like to discuss some possible computer tools which may be useful for students to use when argument mapping. One could be the Microsoft Word SmartArt function. Another could be this mindmapping website: I'd love to hear about any other suggestions. Sam

08/06/2016

Anthony Schmidt

Thanks Sam. I think argument mapping has a lot of uses, and it is a technique that has not been utilized much in ELT. This is likely because few of us have little experience or knowledge of it. Thanks for sharing the mindmap website. It's really cool and I can see a lot of uses well beyond argument maps. Vocabulary lists were the first thing to pop into my mind. Again, really cool! Thanks again.

10/06/2016

Karl Millsom

Eagerly awaiting part 2. Indeed, buzzwords pick up debris as they popularise, and too often eventually they get cast out entirely, the core and sound principles included. This article does a good job of extracting the baby from the bathwater. The argument mapping is something I use a lot here in Indonesia when teaching how to write essays to post graduates who have often not encountered the concept of structured academic writing at all in all their years of schooling. Your examples are very well presented.

30/06/2016

Eric Roth

Thank you for sharing this primer defining, questioning, and contextualizing "critical thinking" in ELT. While many English majors usually choose the essay as the place to teach argument and critical thinking, our EFL and ESL classrooms provide many other opportunities too. Argument mapping is an excellent, flexible technique. In teaching adult education, community college, university, and graduate students, it's also often helpful to deploy problem-solution assignments to develop critical thinking. It can be personal challenge and crucial life skill (staying healthy, choosing a major) or a common social problem (affordable housing, reducing pollution). You can also scale up the vocabulary to fit the situation with risks/benefits, trade offs, and stakeholders. Likewise, asking students to write consumer reviews often works. Consumer reviews provide students with a chance to present facts, express opinions, and provide supporting evidence. Students can also share movie reviews, product reviews, and restaurant reviews online with authentic English-speaking audiences. I've found many ESL and EFL students far more receptive to critical teacher feedback when they plan to share their consumers with the "public" at large, and rewrite class assignments to reach higher standards. Amazon, Yelp, and other review sites have opened up exceptional possibilities and new audiences for student writing. Unfortunately, as the declining level of political discourse in several elections around the democratic world show, critical thinking remains in short supply. Sometimes a powerful slogan - Make America Great Again - can seduce many voters. Would it be helpful for the word "great" to be defined? Would it be useful to know, in some detail, what proposals were being advocated to reach that objective? How will the proposal be implemented? What are the probable costs? What are the likely benefits? What's the timeline? Critical thinking at some level asks students to go from vague generalizations to accurate, detailed suggestions. Numbers add precision. Sources provide credibility. Example illuminate. From my perspective, teaching critical thinking also often requires teaching students to go from the language of false certainty to possibility and probability. Deploying frequency adverbs and hedging language often helps. Thank you, again, for sharing your experiences and research with EFL Magazine readers.

02/07/2016

Anthony Schmidt

Thanks for the reply Eric. You raise many interesting points, all of which I agree with. I find that finding ways of making the audience authentic - not an easy task - paired with critical thinking makes for excellent assignments and student practice. I really like what you said here: " Numbers add precision. Sources provide credibility. Example illuminate." It's a good way to put it and can easily be explained to students in this manner.

04/07/2016

Anthony Schmidt

I'm finding argument mapping to be more and more useful. I have not actually used it for outlining but have used it for breaking down readings, and using the information in the map to inform new writings.

04/07/2016