Experiential/Hands-on Learning in TEFL

Experiential/hands-on learning has long been proclaimed by educators including myself as a fundamental factor in setting children up to have a lifelong love of learning and to perform better academically. But what is “Experiential/hands-on learning,” and how is it beneficial to learners when learning English as a second language?

What is Experiential/Hands-on Learning?

As a philosophy and methodology, experiential/hands-on learning encourages teachers to “purposefully engage with students in direct experience and focused reflection in order to increase knowledge, develop skills, and clarify values.” (Association for Experiential Education, para. 2)

- Experiential/hands-on learning values practice as essential for learning.

- Experiential/hands-on learning highlights students’ experience as the central role for the learning process.

- Learning through experience is also associated with learning through action, learning by doing, and learning through discovery and exploration.

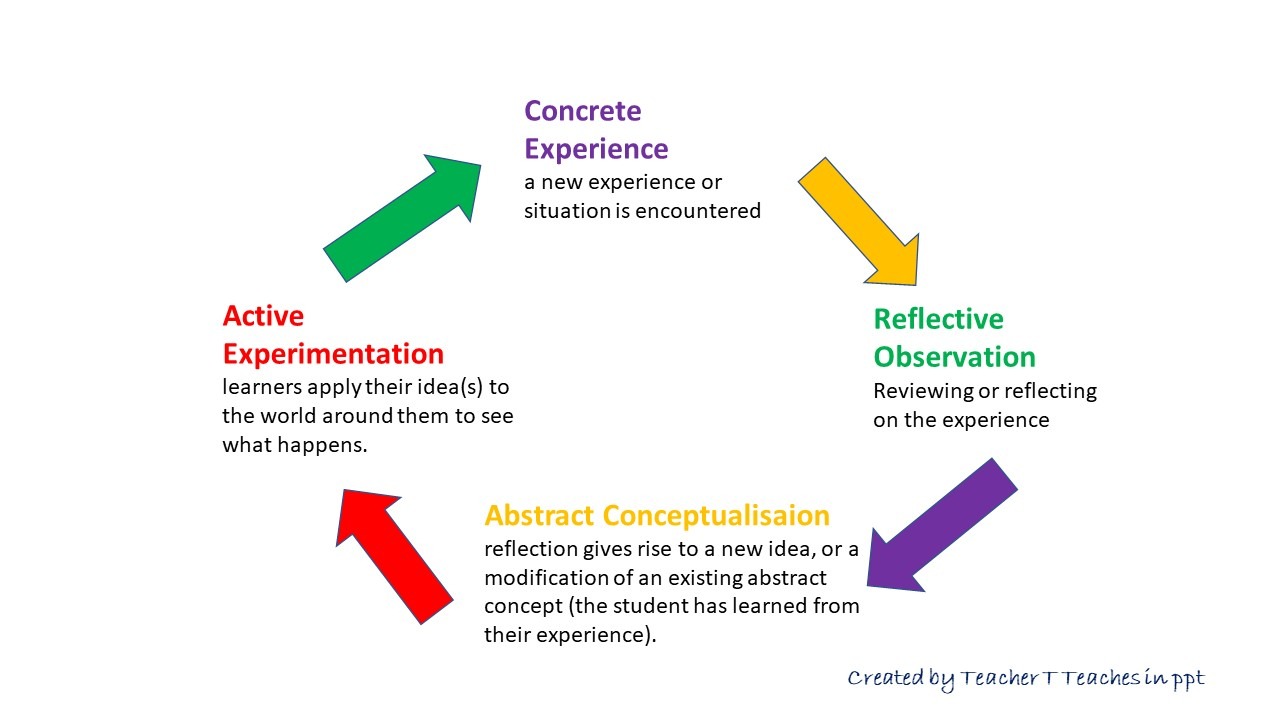

According to Kolb’s four-stage learning cycle depicted in (Fig 1) below, immediate or concrete experiences is the basis for observation and reflection. This reflection is assimilated and distilled into abstract concepts from which new implications for action can be drawn. These imply– cations can be actively tested and serve as guides in creating new experiences. (Kolb, 1984)

Using Experiential Theory effectively in ESL

In many English classrooms all over the world, students are engaged in activities in which they are being exposed to, and provided exercises to practice the language in a variety of activities. These activities mostly provide students with concrete experience to learn the target language. However, there are some criteria on how experiential learning should be implemented in the ESL classroom.

In the field of second-language acquisition (SLA), the experiential approach encourages learners to develop the target language skills through the experience of working together on a specific task, rather than only examining discrete elements of the target language. With regard to the phase of reflection that follows such experience, students are then required to actively engage with their own past experiences and focus on the future (Knutson, p. 53). In addition to students’ language development achieved through the experience of working together to practice the target language, experience learning implies many other potential benefits for SLA in terms of motivation, investment, and cultural understanding.

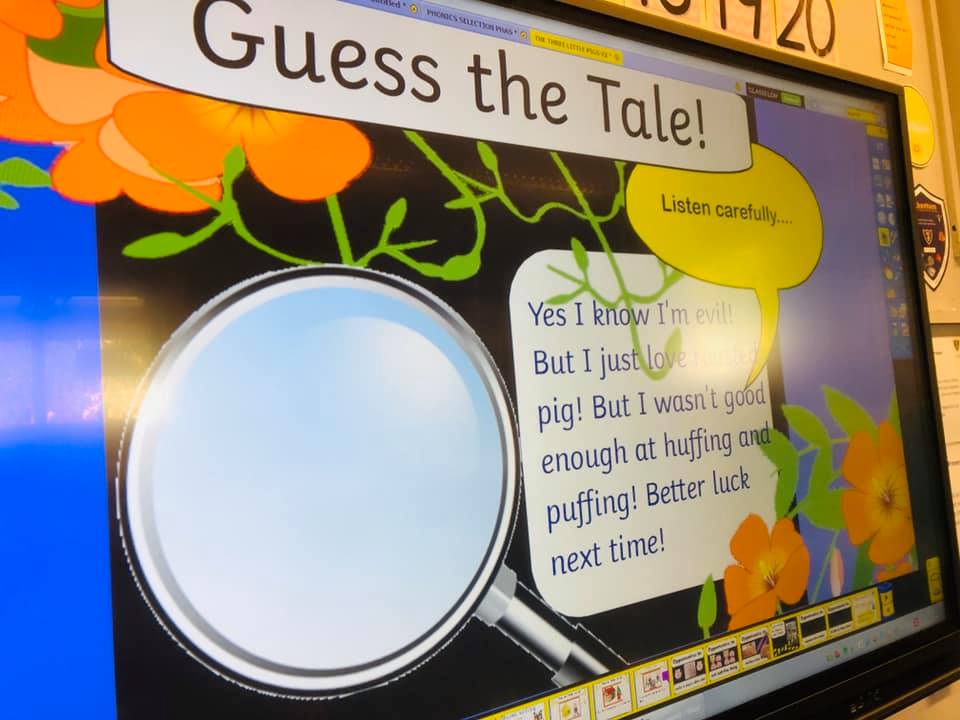

There are substantial language activities or approaches that correspond with the experiential learning approach. On the one hand, those approaches tend to be learner-centred by nature which include hands-on projects such as nature project, STEM/STEAM projects, computer activities (especially in small groups), research projects, cross-cultural experiences (campus, dinner group, etc.), field trips and other “on-site” visits such as a supermarket visit, role plays and simulation -Such as those shown in (figure 2 and 3).

On the other hand, there are some teacher-controlled techniques which may be considered experiential. These techniques include the use of props, realia, visuals, show-and-tell sessions, game playing which often involve strategy, and singing and utilising media such as television and movies (Brown, p. 292). (Figure 4) shows an example of this.

Adaptations To The Learning Cycle in English Language Teaching

As depicted in figure 1, Kolb’s experiential learning cycle entails four elements beginning with direct experience, followed by reflection, forming abstract concept, and finally, testing it in a new situation. This cycle is easily adaptable to a wide variety of educational settings, especially to classrooms where project-based and task-based learning are designed as the core learning models.

Based on Kolb’s four elements, Koenderman (2000) provides an experiential learning model that is a series of phases that outline the sequencing of classroom activities from the introduction of a topic or theme to the conclusion. He then proposes four phases: exposure phase, participation phase, internalisation phase, and dissemination or transfer phase.

- In the exposure phase, a topic is introduced, and students are given the opportunity to reflect on their own experiences in this area and to relate the topic to their personal learning goals.

- In the participation phase, the students become personally engaged as they participate in an activity, either in the classroom or outside, intended to build on or enhance their previous experience.

- In the internalisation phase, a debriefing exercise is initiated by the teacher, and the students have the opportunity to reflect on their participation in the activity and discuss potential effects on their future behaviour or attitudes.

- In the dissemination or transfer phase, the students apply and present their learning, linking it with the world outside the classroom.

Experiential leaning in the ESL classroom builds on the principle that language learning is best facilitated when students are co-operatively involved in working on a project or task, and when the project includes the four above mentioned phases of exposure, participation, internalisation, and dissemination.

TEFL teachers can adopt Koenderman’s phases when teaching their ESL learners in the following ways:

- Exposure phase Students are initiated into the project or task in a manner that will activate their background schema, past experience, and previous knowledge about the subject of the project. This phase offers explicit and effective techniques to activating schemata. Through the exposure phase, students are given the chance to understand the objectives of the activity and to set goals for themselves. The role of teacher in this phase is to direct the class using elicitation questions to encourage reflection on students’ past experiences and relate that to the new topic or activity.

- Participation phase. This phase provides concrete experience or actual activity. Since it is designed as project based or task-based learning model, students are encouraged to work collaboratively in a group. Students are then actively involved in direct experience by using the target language communicatively with their group peers.

Richard (2001) highlights that through engaging students in task-based language learning, it provides better opportunities for real communication. Students learn language by interacting communicatively and purposefully while engaged in the activities and tasks.

Second language acquisition (SLA) theory supporting this phase is Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of the zone of proximal development (ZPD) that refers to the gap between students’ current ability and their potential ability with peer or mentor guidance. The application of Vygotsky’s theory in SLA context has shown that learner-learner interaction is indeed beneficial to ESL students.

In addition, the central role of the teacher in this phase includes:

(a) selecting, adapting, and/or creating the task themselves and then forming these into an instructional sequence in-keeping with student needs, interests, and language skill level.

(b) preparing students for tasks including clarifying task instructions, helping students learn or recall useful words and phrases to facilitate task accomplishment, and providing partial demonstration of task procedures.

(c) raising consciousness in the sense that the teacher employs a variety of form-focusing techniques, including attention-focusing pre-task activities, text exploration, guided exposure to parallel tasks, and use of highlighted material. (Richard, 2001, p. 236).

Internalisation phase

In this phase, the teacher plays the role of facilitator to help students reflect on their language learning experience in the participation phase. The teacher must skilfully ask questions to help draw students’ attention to their feelings and participation in the language learning experience.

This reflection seeks to involve the emotions and identity of the learner. During the internalisation phase, students are questioned about their own language-learning and how they feel it has progressed, as well as how they feel they contributed to their own progress.

Although the teacher sets up the questions, no answers are provided, and the teacher should respond in a non-judgmental way to all contributions from students. This phase closely links to the techniques of Community Language Learning (CLL) developed by Curran (1972) that is called reflection on experience (Larsen-Freeman, p. 104).

At this stage, the teacher gives students the opportunity to reflect on how they feel about the language learning experience individually as learners, and also in their relationships with each other. The teacher’s non-judgmental response in this

phase can encourage students to think about their unique engagement with the language, the activities, the teacher, and the other students, and strengthen their independent learning.

Dissemination or transfer phase

This phase is the final stage of experiential learning. This phase is very important in helping students to link the classroom learning with the real world outside of the classroom.

It is widely recognised amongst ESL teachers and researchers that there is need for language-learners to be able to transfer their classroom experience into their day-to-day contexts. The demand placed on language learners and teachers to make a clear link between the classroom and the world outside is undeniable. Consequently, projects or tasks may culminate in a role-play of a social situation in class or by students going on a field trip to practice newly acquired skills.

Student experience is valuable and meaningful for their language learning. Through project-based or task-based activities, the experiential learning phases allow students to directly experience the use of real communication in a mock scene, to reflect their feelings and language learning experience, and to enable them to link and transfer their experience in the classroom into the real world.

Do you incorporate experiential language learning approaches with your ESL learners?

What do you feel are some of the disadvantages and advantages to this approach when Teaching English as a Foreign Language?

References:

Association for Experiential Learning, retrieved from http://www.aee.org/

Kolb, D.A. 1984. Experiential Learning. Englewood, NJ: Prentice-Hall

Knutson, S. 2003. Experiential Learning in Second-Language Classrooms. TEFL Canada Journal, 20(2), 52-64.

Brown, H.D. 2007. Teaching by Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy. New York: Person Education.

Richard, J.C., & Rodgers, T.S. 2001. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. New York: Cambridge University Press